14. A Bump In The Road

A Bump in the Road

As our little red Honda tears along the road in southern Mexico heading up the coast towards Acapulco, the warm, tropical air flows in through our open windows. After two weeks of travel, we relax into the rhythms created by the green trees and farmers’ fields that flash by the windows. We zoom past children in their blue and white uniforms, book bags on their backs, as they head towards school. A bike wobbles past on the barely-existent shoulder.

A tall Pemex gas station sign looms ahead and small houses and shops start to thicken along the edges of the road. Then the triangular yellow sign appears by the roadside. It is wordless but its three mountain-like symbols carry the warning. Gary slows the car, and we scan the road for the obstacle we know is coming. It’s there, the tope (TOE-pay), the dreaded speed bump, that gives power to the humblest of Mexican towns. The Mexicans call them “policía durmiendo,” sleeping policemen. We creep forward, coming to a virtual stop as the front wheels hit the slope and we begin to climb.

After thirty years of Mexican travel, much of it by car, we still grit our teeth as our “destination fixation” causes us to resent these intrusions on our time schedule, but we have come to accept and even admire them as a basic part of the culture. They demonstrate to us the character of a people, the people of village Mexico, who love their children and who have found a low-tech solution to protecting the little towns and communities of Mexico. A well-placed tope can bring a huge eighteen-wheeled rig to its knees, forcing it to a stop before it crosses the town boundary. The chickens are safe to wander across the road, mothers with toddlers stroll casually, and bicycles beat the big rigs by cutting around the end.

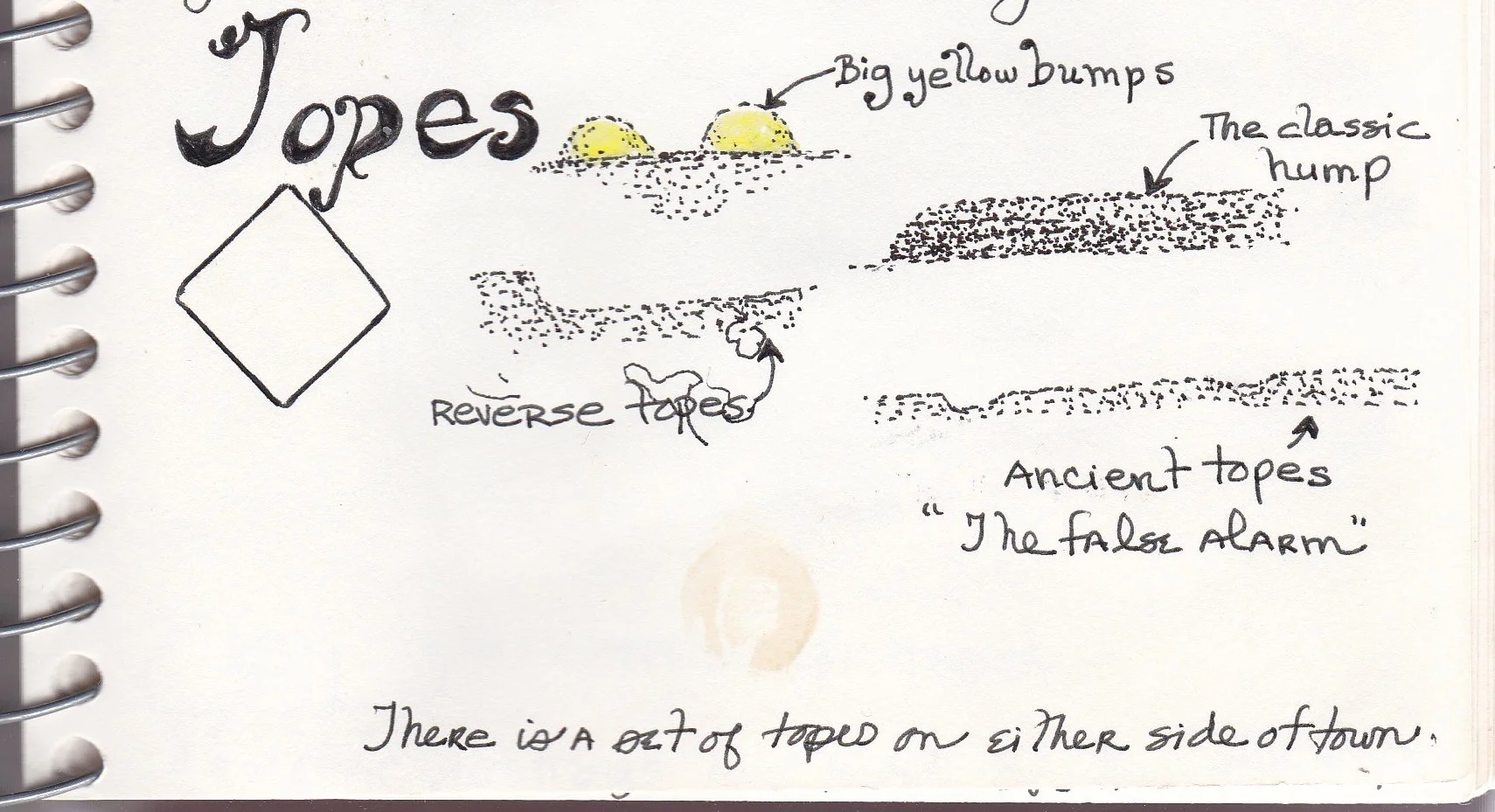

Over the years, we have become connoisseurs, viewing tope crossings as another cultural experience to savor on our drives south. We even devised a classification system. We use the ocean surf to classify the topes we encounter. The easiest to navigate are the rollers. Professionally built by road crews, they are wide and rounded, the tops slightly flattened. Most are sculpted from smooth black asphalt. Even at high speed, our Honda maintains its equilibrium as we roll over the top and down the far side. We welcome the rollercoaster ride they provide.

A little tougher are surf topes. With a touch of humanity, there is usually a warning sign which tells you how far till you hit. Often painted with stripes of a contrasting color, you can see them coming. Most are built by road crews, but unlike the rollers, the rise is steep, the top narrow. These topes demand your attention. If you feel you can beat the game and sneak around the end, you almost always find an obstacle, a giant rock or a piece of metal, barring your way. The surf stretches all the way across both lanes so you can’t slip into the oncoming lane to escape.

Rougher yet are the breakers, the improvised topes. A few reinforcing rods, a pile of cement, slop it on the road, then listen to the hiss of airbrakes as mighty trucks halt and creep over these killers. Some come to a point at the top. Others are studded with metal projections, or half cannonballs placed along the top edge, spaced so you can’t avoid them. The breakers love to scrape the bellies of cars like our little red Honda as it tosses us over and out.

Gary and I both have our favorite topes and our most hated. My personal worst are the triple triangular topes, the t-t-t’s. These merciless beauties come to a point on the top. Your front wheels hit a wall, climb to the apex, hang momentarily and crash off the other side. You brace for that fall and wait for the next…and the next.

Breakers can be made out of many materials. Chains, hawser-like ropes, lines of rocks, drain pipes, fire hoses, the treads of giant trucks, they all serve the same purpose. They may be built to reflect their location. We have encountered cobbled topes on the streets of colonial San Miguel and dirt topes in the tiny village of Teacapán in Sinaloa. We have found handcrafted topes on roads that are so rough, so potholed, that you can barely move anyway, defying logic. You may even encounter a soft tope made of still-warm asphalt in areas of road construction.

The deadliest of them all is the sneaker tope. Almost invisible until you hit, there is no time to break, no time to brace your body. I may get out a desperate, “Tope, tope, TOEPAY,” but we go over at full speed. A moment of elevator-stomach after the rise and we hit hard on the other side, springs compressing, our heads nearly hitting the roof of the car. Sneakers love to lie hidden in the shadow cast by a tree, making morning and evening their favorite times.

A category we are encountering more frequently on our drives south is the phantom wave. I spot a sign, “Reductor de Velocidad a 100 m.” Gary and I scan the road, finally seeing the telltale stripe on the pavement ahead. We slow, preparing ourselves for the confrontation and brace for the hit. Nothing happens. We drive over a yellow line, conned by the ruse. The town is safe, they have avoided the expense of building and maintaining a tope, and we fume at the injustice of it all, yet are impressed by their ingenuity.

Topes have become an integral part of the culture, providing citizens with entertainment and a market for their goods. Just set up your stand at one end of a tough one and the world comes to a stop at your door. Brooms and dust rags in Calpulapan, dried shrimp and cold coconut milk along the coast, fresh-squeezed orange juice, tortillas, pyramids of tiny peaches, and baskets of strawberries in Michoacan, baby quail and quail eggs in Cuautla, home-made paper and plastic kites with long streamers in Puebla, where vendors hold out fuzzy puppies no more than a handful big. Entrepreneurs hawk their goods to the lumbering trucks and cars that creep over a big one.

A tope is also a good place to put your wheelchair so you can collect for medical bills, a place to ask for money to support the Red Cross, AA, or drug-rehab programs. A one-legged man is hard to resist as he stands atop a tope with his collection box on the road to Zachilla in Oaxaca.

As superhighways—70-mph asphalt rivers with toll plazas and four lanes—slice across modern Mexico, our drives south are faster, more comfortable and safer. We pick up snacks and drinks in Oxxo chain stores and have lunch at The Italian Coffee Company or Subway. But on the slower byways where the ocean roils, we still savor the challenge. We pull into a little town where one of the elders has set up his plastic chair at the end of a breaker tope. On a dull day he can watch the world pass, see our car, and think to himself, “Look at those gringos in that little red car. Boy, they are gonna scrape on this one.” We slow professionally and flow over the big one without a hitch. We drive on, grateful for this other side of Mexico where the culture of the tope is alive and well, where we’ve been slowed down enough to appreciate the real Mexico along the way.

* * *

All Content Copyright ©2020 Linda Oman | All Rights Reserved