13. The Ring Road and Other Highways

The Ring Road and Other Highways

Sharing the Road with the Big Rigs

Half-way to Hermosillo, we passed a northbound line of trucks about two miles long that were stopped in the left lane for a military checkpoint. The median was littered with plastic bottles and trash from those who had come before. We have found that almost all of the military checks are on the way north. No one is concerned with the trucks that head deeper into Mexico. They also seem unconcerned that the truck drivers have to wait endlessly in the huge lines.

The drivers sleep, listen to loud ranchero music, socialize, stand next to their trucks, peer impatiently down the line, eat snacks, some provided by enterprising locals. I notice that most of the trucks are big, modern semis, some even “doble semi remolques,” double trailer trucks. There are a few of the classics, the slat-sided trucks that have decals with a loved one’s name or a saying on the back, the ones that creep up inclines with bulging loads secured by rope. We always used to laugh at the trucks where you could see the front and the back at the same time, as they had bent frames.

On one of our trips, we passed an open-sided truck loaded with pigs. They were packed in, one unfortunate guy sent aloft, riding the top of the truck with his legs stuck down through the slats on top. Sad and frantic, his ears blowing back in the wind, he was a living bow sprit on the asphalt sea.

That trip, one of the trucks had strayed too close to the shoulderless edge of the road and the trailer had slid down the embankment. A very large tow truck was straining to pull it up. Further along the road, the shell of a big semi had strayed into the median ditch and hadn’t been so lucky. There was no sign of the cab of the truck, and what was left of the driver was long gone.

* * *

Rest Stop Adventures

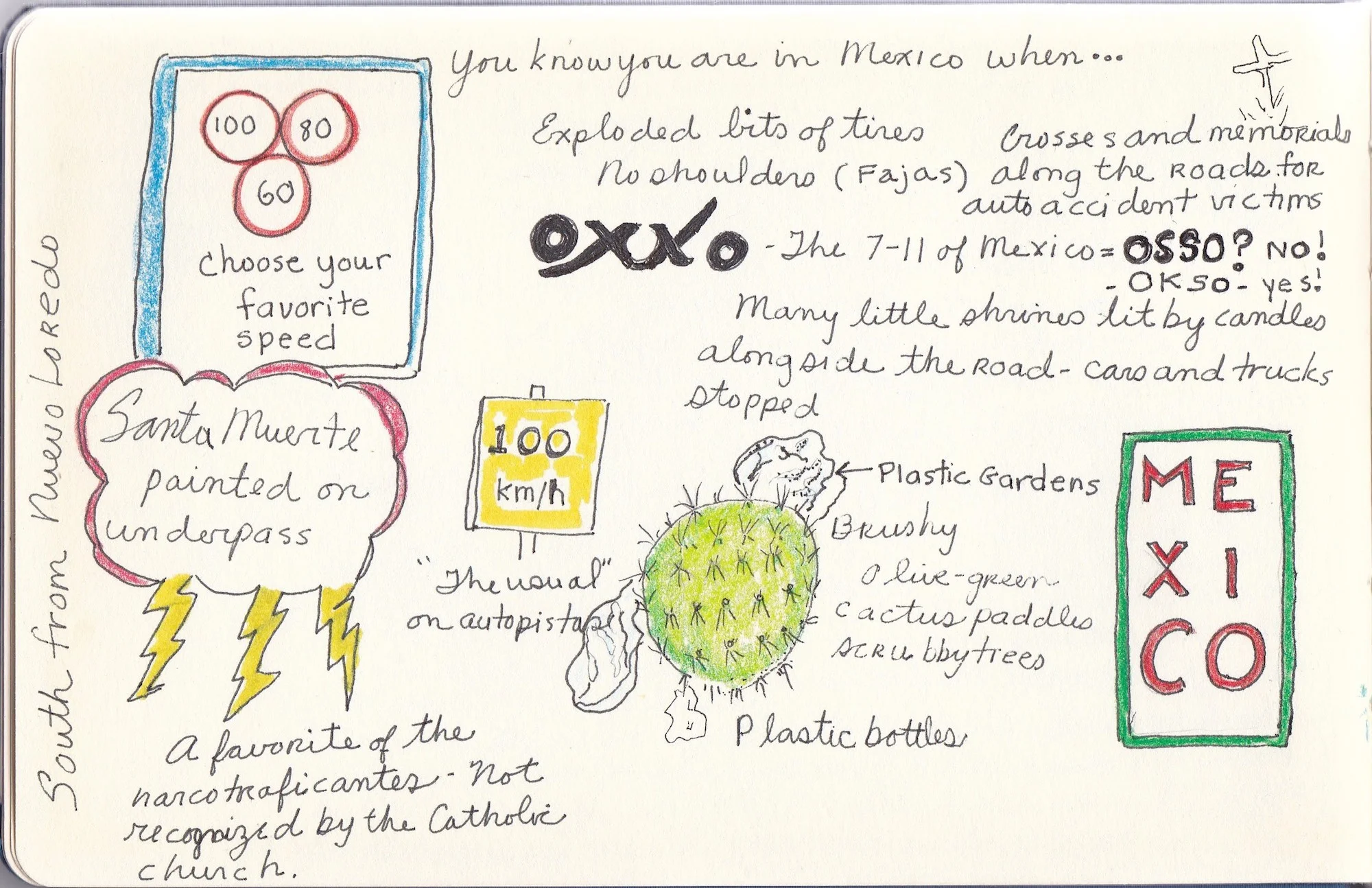

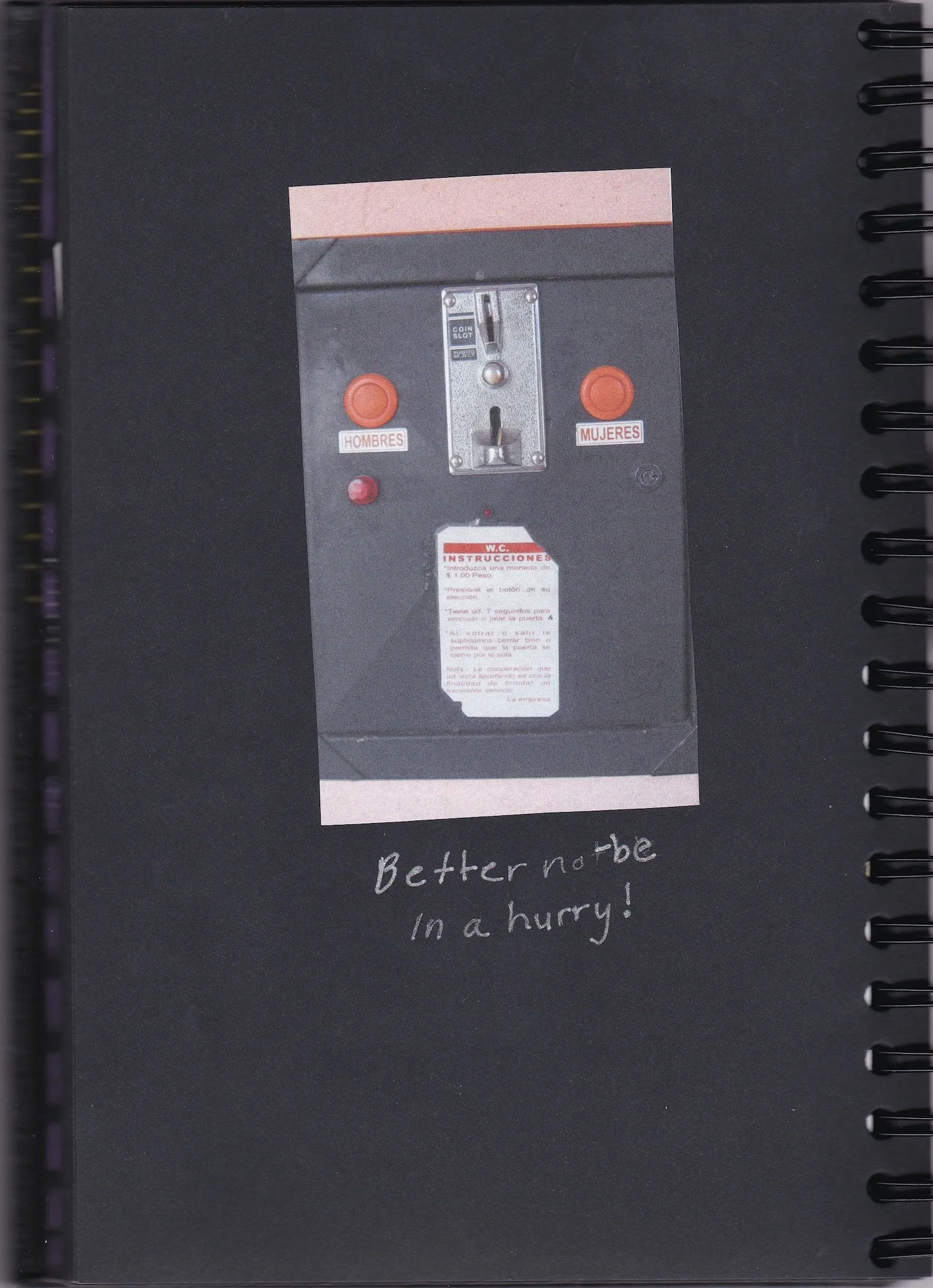

Seasoned Mexico travelers soon learn that Pemex gas stations are Mexico’s rest stops. After traveling through Mexico for over thirty years we have applauded the advances in Mexican sanitarios. We can remember the times when they were unsanitarios, where attendants handed out squares of newspaper next to doors that led into dark and odoriferous cubicles.

Modern bathrooms are well-maintained and often have huge rolls of paper, usually chained to the wall as they seem to be a hot commodity. Ditto the door latches. There must be numerous homes in Mexico featuring these stainless-steel beauties. Ditto toilet seats.

Reflecting the dawn of the new era of cleanliness, on the last trip, I read a sign posted next to a sink: “Please wash your hands before and after using the toilet.”

Like the roads, bathrooms have a distinct Mexican character. Sometimes, you have to pay an attendant one or two pesos or plunk coins into a machine that rarely unlocks the door on the first try, especially when you need it to open the most.

Bathroom stops often lead to adventures. I was once escorted to the bathroom by a man in uniform carrying a big machine gun. No one bothered me on that journey.

One time while Gary trolled for snacks, I entered the empty bathroom and chose the middle stall, latching the door behind me. After I used the facility, I went to leave. The stall door would not open. I twisted, pulled, pushed, tried everything, but I was trapped. I examined my options: I could call for help. I could wait till someone came in. I could wait until Gary noticed my long absence. Not wanting to embarrass myself by yelling or asking for help, I eyed the space under the door. It looked like a fit. Lying on my back next to the toilet, I experimented with my head and shoulders. I had just enough space. Out I scooted. Luckily, the floor was clean (looking) and no one came in to see my prone, sixty-two-year old body, sliding across the floor. Having experienced rebirthing from the womb of a bathroom stall, I dusted off my clothes, washed my hands, and got out of there, leaving the stall door locked from the inside, a mystery for the attendants to solve. Gary was sitting on a wall outside, snacking on an ice cream bar. He nearly choked on his “Mega Almendras” as I recounted my adventure.

* * *

Close Calls

My most hated stretch of highway is the section between Mazatlán and Tepic. The highway starts out four-lane divided and deteriorates into a two-lane horror where you can be stuck behind trucks that seem to make little headway. Your alternative is to pass, looking for a break in the long lines behind lumbering trucks coming the other way. Luckily, we started at eight in the morning. We have found that things don’t get going in Mexico much before 9:30 or 10. Also, the weather was cool and cloudy at the beach, so the road was free from the usual speeding weekend vacationers from the central plateau. I remember one time when we hit it wrong and found ourselves constantly behind the creeping lines.

When we got to a clear stretch with only one car in front of us, we witnessed a close call, as a car coming the other way tried to pass. Realizing he wasn’t going to make it before smashing into the car ahead of us, he turned off the road and luckily ended up at his balance point, tilted sideways down the embankment. The two men driving the vehicle in front of us were very understanding and helpful to the two suspended occupants of the other car.

We drove on only to discover a sea of tomatoes strewn down the embankment on a curve. The tipped truck had been towed away. This stretch is about to be replaced by a divided four-lane superhighway that will speed up the trip and make it safer for those able to afford the tolls.

* * *

We left the autopista at Escuinapa, about two hours south of Mazatlán, and headed towards the tiny fishing village of Teacapán. Back on two-laners, we discovered the highway was not done with us yet. The roadbed was narrow, shoulderless, and elevated. As we watched the pickup truck ahead of us accelerate and move into the opposite lane to pass a slow vehicle, we could both see that he wasn’t going to make it. He hit head-on, careened off the front bumper of the oncoming car, shot across the road and down the embankment, knocking down a telephone pole. He then spun around, facing the other way. Amazingly, he climbed out of the truck and walked up the bank, then started up a quite lucid conversation with us. Other than a swollen eye, he showed little sign of serious injury. Most Mexicans ignore seat belts, so his escape seemed even more miraculous.

We helped the best we could, asking a taxi driver and a woman in a car with a cellphone to call for help. We drove on, shaken and sad, as we discussed the impact the accident would have on his life—wrecked truck, damage to pay for the other vehicle, doctor bills, and unforgiving police, as he would be charged with causing the accident. He may even be in for jail time. Many people live close to the edge in Mexico and the safety nets we are accustomed to are just not there. We drove into Teacapán that day, thanking San Cristóbal, all Tibetan deities, and the Virgin of Guadalupe for keeping us safe.

* * *

Riding the Ring Road

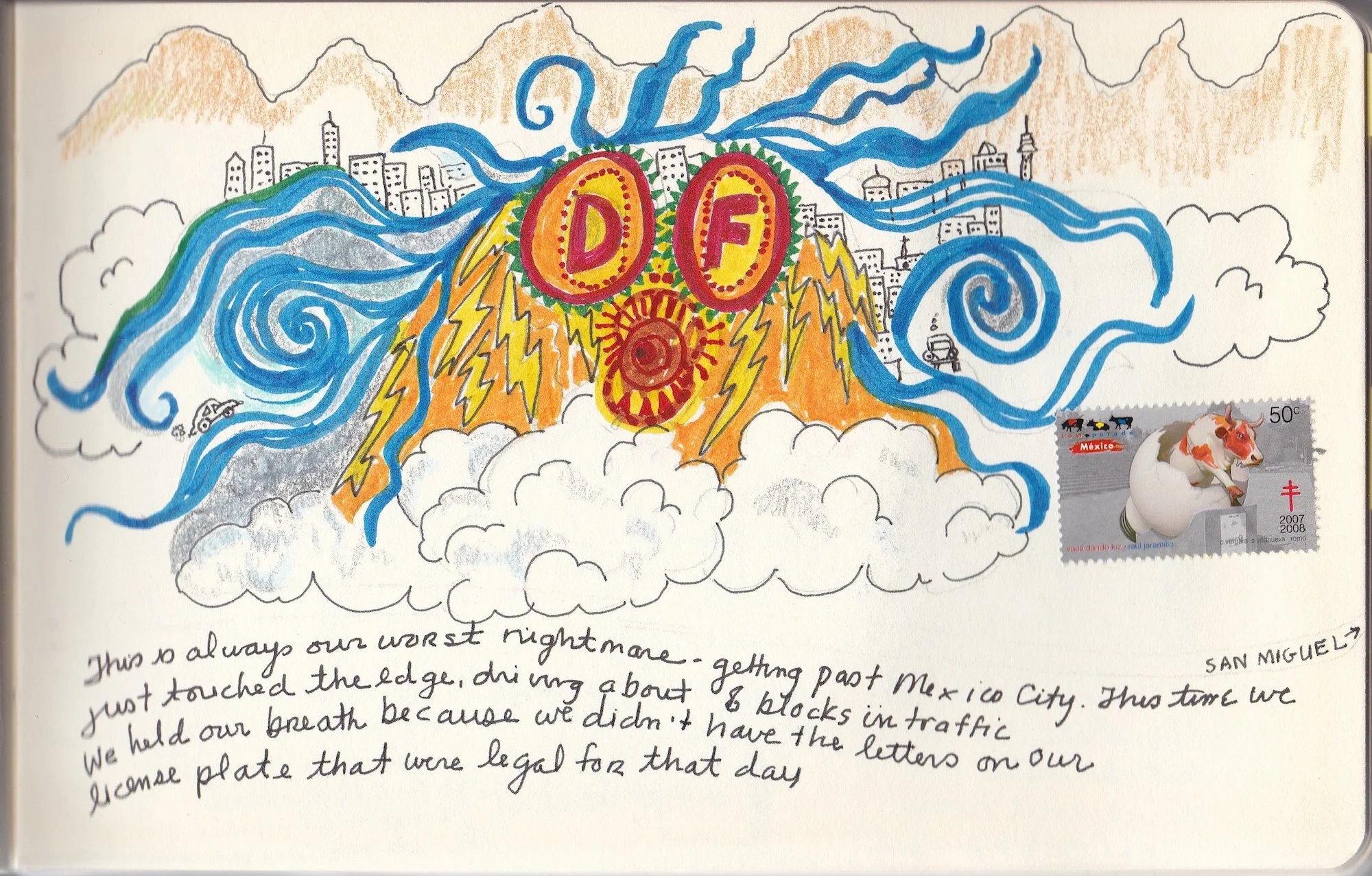

One year we’d been gone a month, and having fallen into the rhythm of Mexico, were primed to expect the unexpected. The morning traffic into Mexico City was just beginning to build. As we went to turn onto the main highway, we passed a woman dressed in a business suit and high heels, standing in defeat next to her sub-compact Hyundai Atos. She had run over a manhole cover that had given way under the mighty weight of her car, plunging one doughnut-sized tire into the depths.

Driving through the outskirts of Mexico City we marveled at the pollution, now mixed with early morning winter fog, that had settled in the low spots. This hazy layer, a product of automobiles and innumerable belching factories, was with us for miles.

The houses thinned out and we drove through pastoral countryside, ascending into the pine forest. We stopped at a “mirador,” a lookout, to view the sulfur vents on the side of a volcanic peak. And to view a garbage dump, created by the myriad travelers who had stopped to look at this wonder of nature.

* * *

We got back on the road, anticipating a glorious drive through the countryside (it was), and a fun time in Toluca (it wasn’t). This suburb of Mexico City, population half a million, has never been our favorite, as we have spent too much time in the past trying to discover where we were and failing. We had high hopes this time, however. As we reached the outskirts of the city, we were discussing how we could manage to find a hotel in the maze of unfamiliar, unmarked streets packed with racing traffic. I had a Guía Roji, the Mexican bible of the road, on my lap open to an enlarged and totally incomprehensible map of Toluca. Suddenly, we heard a siren behind us. A squat white police car, lights flashing, was on our bumper, signaling us to stop. Naturally, there was no shoulder on the road, so we made one of the outside lane.

Three policemen got out of the car and circled us. I watched as a stereotypical Mexican policeman—black mustache, big khaki-covered belly riding over a belt decorated with dangling gun and nightstick—eyed our army green duffels stacked on the back seat, and inspected the collection of cactuses sitting in the back window. He couldn’t hide the smirk that spread across his plump face as he assessed how much money he could extort from the wealthy gringos.

Responding to the curt gestures of the head man, Gary rolled down his window. Having been warned by other unfortunates not to speak Spanish, Gary started a pidgin-English conversation. Macho Man said we were going over the speed limit (NOT). He wanted a license. Prepared for just such emergencies, Gary whipped out the fake wallet he always carries. Fearing the police would take the real thing as hostage, he handed over an expired license, the one you get back with a big hole punched in the middle. Unfortunately, the officer understood the universal language of numbers and announced in glee that we were driving with an expired license. Gary mumbled and fumbled and was forced to produce the real thing.

“How much is the ticket?” Gary asked in defeat.

“1,200 pesos,” almost US$120.

“No way. Give me the ticket and I’ll go pay it,” Gary countered, hoping to call his bluff.

Unwilling to write out a ticket and lose his cash bonus, the policeman played his ace in the hole. “We will tow away your car,” he snarled, no longer calm and official.

At this point, we knew we were goners. We were going to have to produce the “mordida,” the bribe. Gary backpedaled, fumbled in his wallet (which luckily didn’t have much money in it) and offered him $40. The policeman grabbed it surreptitiously, doubtless aware of the scores of witnesses whipping by at speeds above the posted limit. He stuffed it in his pocket and waved us on.

* * *

Highly irritated, hating Toluca, we wove our way through a nightmare of nameless streets, and finally, by some miracle found the main highway. We pulled into a hotel that looked like a good possibility, and headed into the driveway. The hotel rates were reasonable, $30 for a double. We drove into a long, covered area with rooms on either side. Each room had a garage underneath with a staircase in the back and a door that closed behind your car. We pulled into a garage so we could go in and register. An anxious young man came running towards us. He waved us out of the garage and pointed to an area at the front of the main building. We re-parked and went up to the desk to check in, asking for one of the rooms we had just seen.

“Those rooms are rented only by the hour,” the desk clerk told us. It was then that it dawned on us that we had driven into one of the popular motor hotels reserved for Mexican men and their mistresses. The doors on the garages prevent “the little woman” from snooping around, looking for her wayward husband. The $30 was an hourly rate. We ended up paying $70, breakfast included, for a very nice “family room” in the main building.

It was still early, so we took a taxi downtown to see the botanical gardens. We ended the day with a great dinner of enchiladas and quesadillas, and we watched a passable movie on our motel television. Despite our trials, we slept well that night. It had been just another day on the road.

* * *

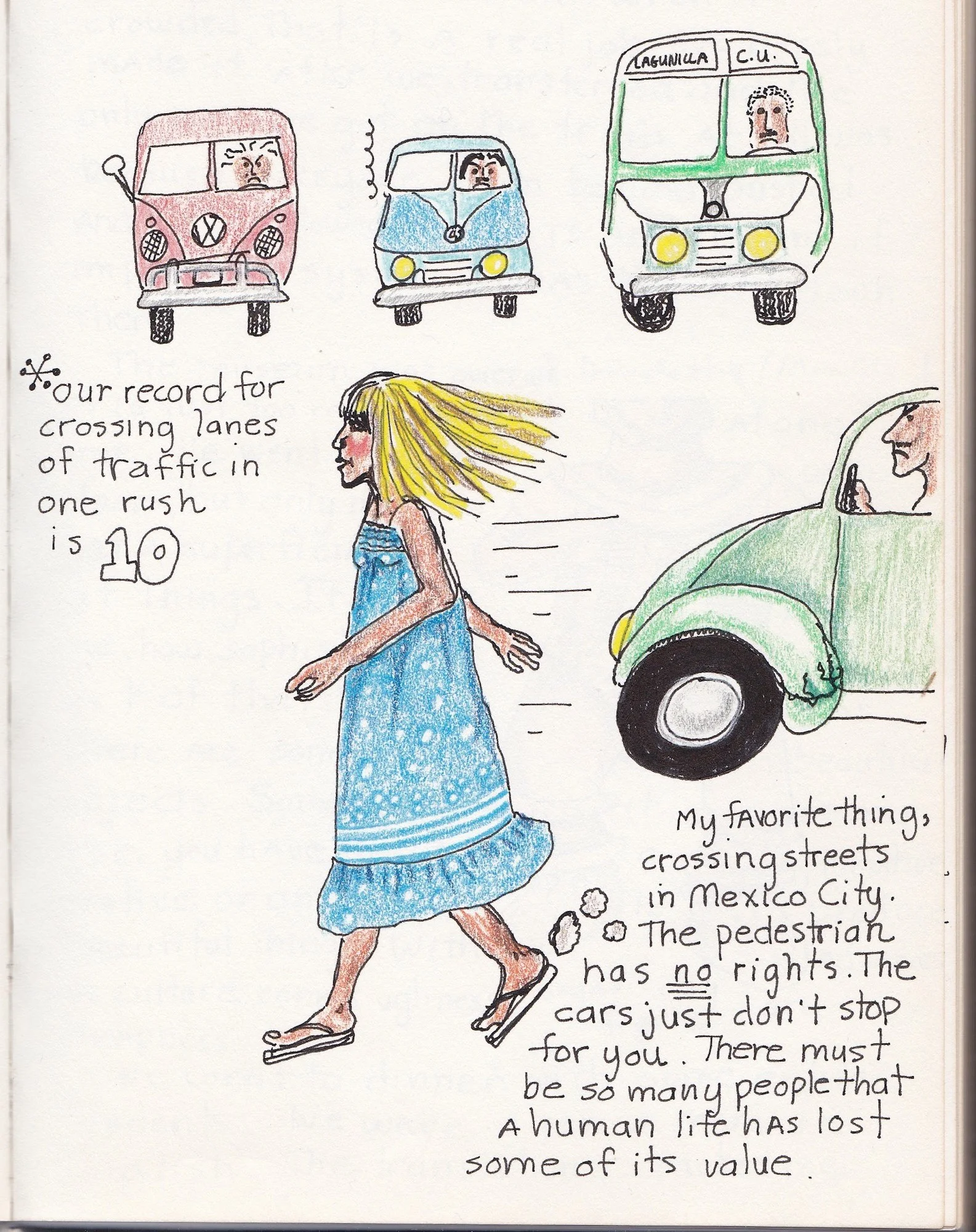

I have always had a great fear of crossing Mexican streets. The pedestrian has no rights and it is often safer to cross against the light or even in the middle of the block. My body clenches as I cross multiple lanes in a pedestrian zone. I can hear the drivers revving their engines, can feel the tension as they sit, foot poised above the accelerator. As happens in the United States, Mexican drivers are also red-light runners, figuring that if they get across just ahead of the cross-traffic, the game is won

This year, they have installed a new kind of crossing light on the busy Avenida Niños Héroes de Chapúltepec. These lights use the countdown system found on many of the new crossing signals in the USA and Canada. What amuses me is the little man that turns green to let you know it is safe to cross. In Mexico, he is animated. He runs. Boy, I can really identify with that. Fear makes a great prod.

* * *

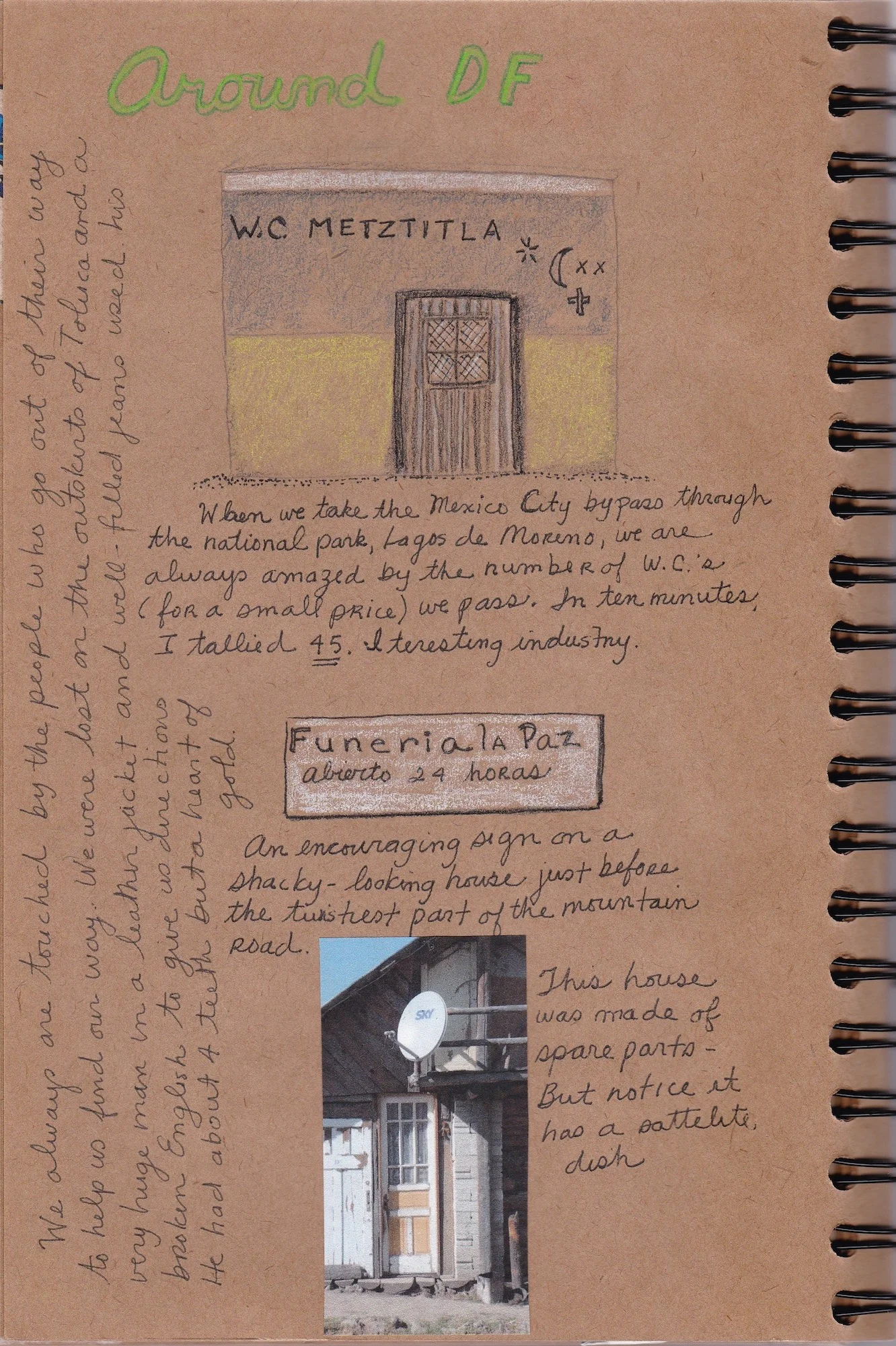

The first time we ever arrived in Toluca, by sheer luck, we hit the ring road. We get lost and hire a taxi driver to lead us through to the little road we hope will start us on a route around the Distrito Federal of Mexico City. We creep through millions of little towns, all with topes, tortas, tortillas, loud music-markets, no signs except an occasional teaser that leads us down a dead end. We head into a pine forest. Most of the stands along the road seem to be advertising clean WCs. Also sheepskins, “barbacoa,” barbecue.

We head into high mountains, twisting on a narrow road that has a new covering of gravel—no tar yet, no shoulder, shear drop-offs, no guardrail. We look two thousand feet down. There are ten crosses clustered. We meet a car over the center around a curve. The driver corrects and skids in the gravel close to the drop-off. We pass giant trucks. It is getting dark and we look up at high peaks and down into deep valleys. It reminds us of the Pacific Northwest. Finally we hit the road to Cuernavaca. We see the lights in the dark, way below. We endlessly twist down the mountain and get lost in the city.

* * *

Gallery

Click on images to enlarge…

All Content Copyright ©2020 Linda Oman | All Rights Reserved