9. A Mountain Angel

A Mountain Angel

Finding the turn to La Unión de Tejalapa is not easy even though we’ve been this way before. After a large billboard displaying a huge golden bottle of El Sol Beer, we look for the unmarked road. Surrounded by frenzied drivers and zooming trucks, cars, buses and motorcycles, we make the turn.

Gabino’s town, La Unión, is at the end of the road where the rounded yellow hills meet the horizon, with a softly sculptured topography dotted sparely with gumdrop-shaped trees. Fluffy, fog-like clouds rest on the crest, blurring the skyline. Only fifteen minutes from our home in the heart of Oaxaca City, this village is worlds away.

We drive to the top of the hill on a narrow dirt track to Gabino’s house, passing a field of dried yellow corn stalks, last summer’s crop. Walking the last few yards to his house, we pass a couple of weaner pigs tethered in rope harnesses. They raise their small, sniffing snouts and grunt in curiosity as we pass. I eye the two dogs that lie in the courtyard of the small house ahead. They are yellow and spotted, lean to the bone like many Mexican dogs, hardly stirring from their sunny spots in the dirt as we near. A petite gray cat, barely a kitten, tiptoes past.

Gabino has expanded his house since our visit a year ago. It is still humble by city standards: three rooms made of cement block, one of which holds Gabino’s carving studio, and an open-air kitchen that projects out into the courtyard. A long table covered by a pink, flowered tablecloth holds a bottle of pop and an unopened quart of tequila.

We greet Gabino’s mother, a gray-haired woman, bent at a permanent angle, toothless, who stirs a large clay pot over an open fire. “Frijoles,” she tells us, beans, the staple food of the Oaxacan villages. Black coffee brews in a second pot. Looking at her brown face wrinkled like a dried apple, I wonder at her age. Is she close to my age, 63? She looks ancient, but the subsistence life in the country puts on the years fast.

Gary calls out Gabino’s name. His son, a teenager in a basketball shirt and blue baseball cap, appears in a doorway. We can see a double bed in the dark room behind him. Even though it is after ten, Gabino isn’t up yet. Gary calls again, teasing about the late hour, and finally Gabino appears in the door. He nods to us, then darts around the corner to splash water from a basin on his face and ram a tan baseball cap on his head.

When he returns he greets us with the traditional handshake. “Estoy medio enfermo,” he tells us, I am a little sick. He sheepishly admits that he drank a lot of tequila last night at his niece’s quinceañera party, a coming-of-age event held when a Mexican girl turns 15. “Ah, la cruda,” a hangover, Gar teases. He recommends a little menudo, a soup made of tripe that is said to be good for curing hangovers.

Gabino is a good-looking man. He is of medium height and has the stocky build of the indigenous people. His hair is sprinkled with gray. Over the four years we have known him, he has developed a “panza,” a “beer belly.” Crinkles appear around his eyes when he smiles, which is often. Today, he is wearing a pink and gray Chicago Bulls’ sweatshirt, a present, he tells us, from a gringa shop owner who buys his carvings for sale in the United States. He speaks rapidly, his lush salt-and-pepper mustache moving in concert with his words. I have to strain to keep up with the conversation. He has the habit of frequently saying, “Cómo se llama,” What do you call it, as he talks. Gabino likes to talk.

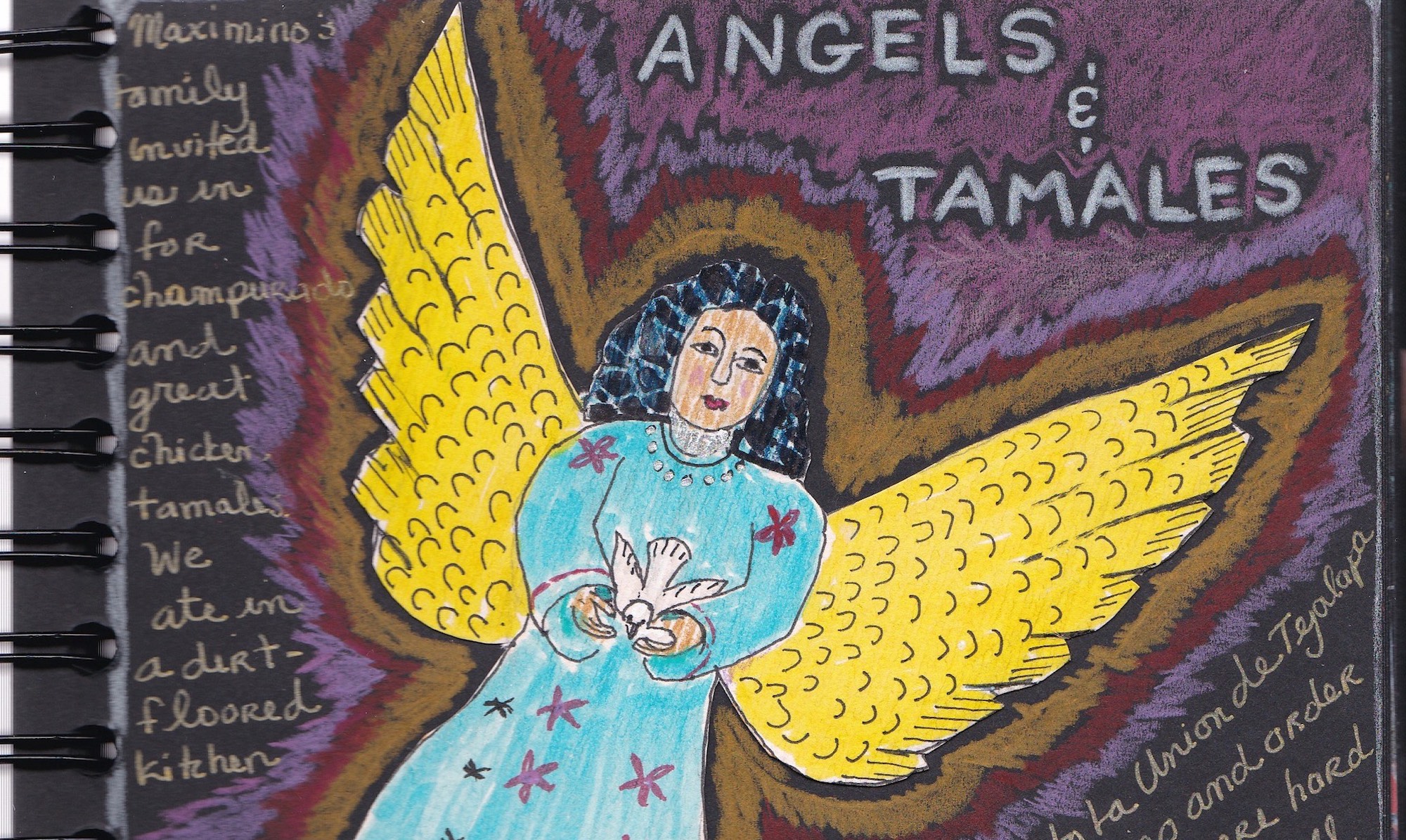

In the last few years, we have purchased two of Gabino’s carvings. With an international reputation he gets good prices for his works. I love the beautiful faces he carves, so we have come to ask him to carve us an angel. We ask if he has anything to show us. “Nada,” he says. The lack of tourists in the city due to the political problems has dried up the funds Gabino counts on to supplement his income.

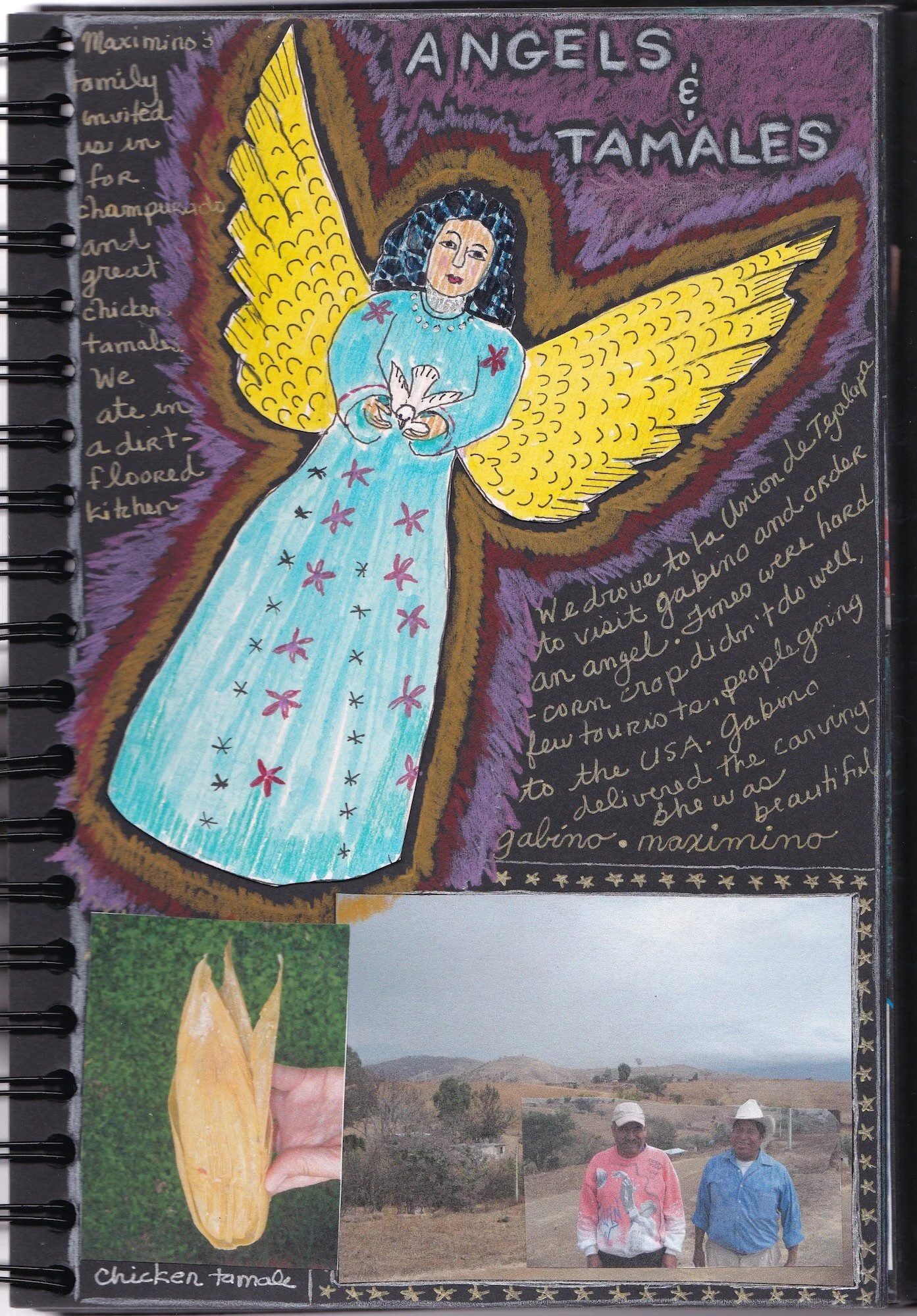

Gabino pulls out an album of pictures as we discuss the commission. He shows us his latest carvings: A slim green cornstalk with delicate pointed leaves. On one ear of corn, cupped in green leaves, is a face of the Virgin in a tiny oval no bigger than my thumbnail. The second is a mazorca, a corncob, with the virgin emerging from the sheltering husks. We describe the figure we want, a Mexican angel with the beautiful dark skin of the Zapotec people. We agree on a price and a finish date, but we don’t bargain. His pieces are beautiful and we feel it would be insulting to offer less.

Conversation is friendship in Mexico, so we settle into a discussion about affairs of the village. Gabino talks about the conflicts, the rising price of corn, the difficulties he has had with his crops this year. He doesn’t have much land to farm and he timed his planting wrong. His corn dried up and was only good for animal feed. Then the tourist market disappeared. His words add to the burden I have felt since we arrived in Oaxaca. The riots are over, but nothing has been resolved. It is people like Gabino who have been punished. It is a sad time.

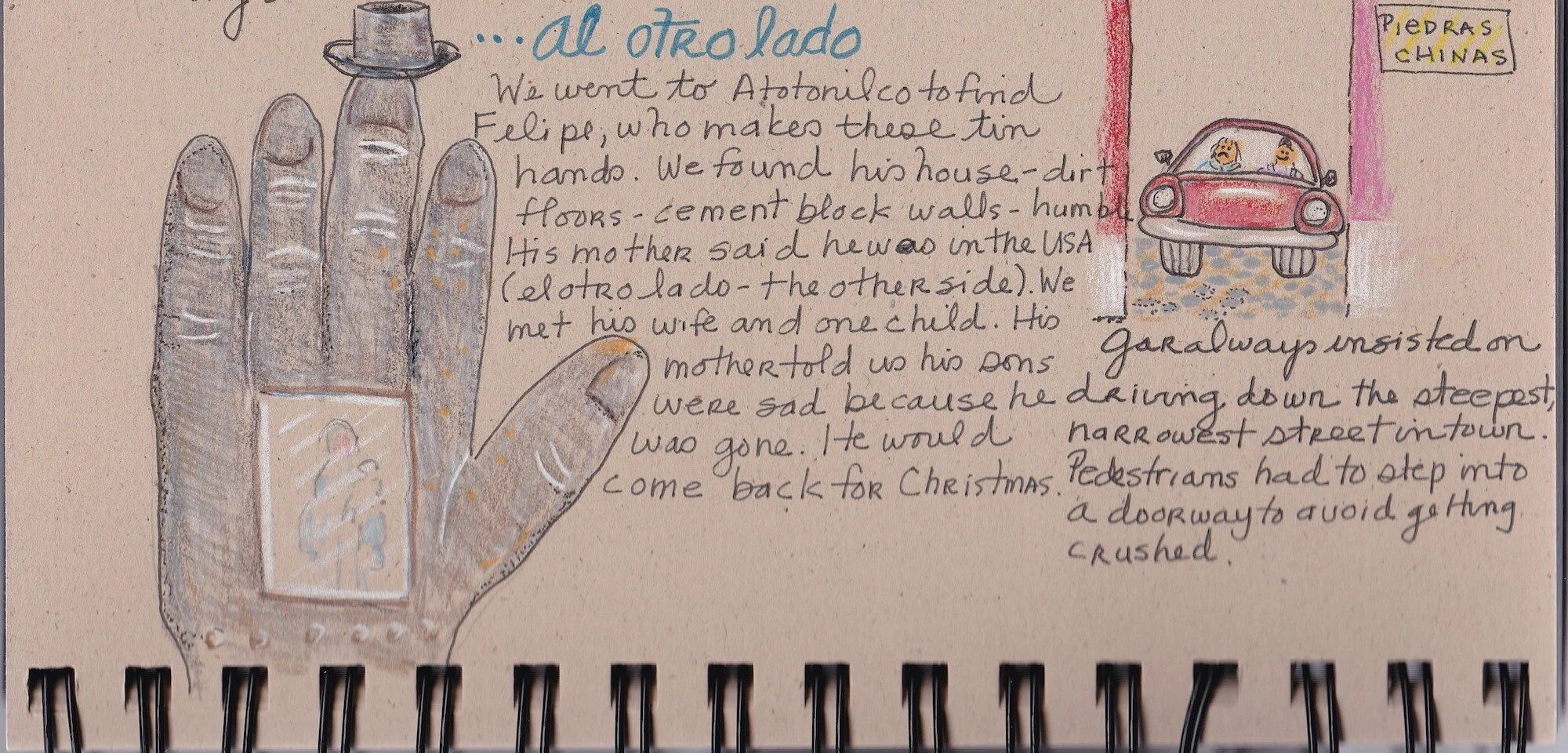

We discuss immigration. Gar points to a house of cement blocks on a hill nearby, a house that is more spacious, with windows, and a second story. Gabino tells us this man went to El Norte and sent back money to build this fancy house. Now his wife and family sit alone while he works in the United States. His children have no father to guide them. His wife has no husband to help with family affairs. Gabino tells us that some men even desert their wives and take new ones in the United States. Many Mexicans call our country “El Otro Lado,” The Other Side. It sounds like a place where you go when you die. Maybe it is a kind of spiritual death for many Mexican families. Gabino tells us when men come home again, they are often filled with discontent because they work as hard as they did in the United States, but they earn a fraction of the salaries.

Gabino offers to take us to the house of a friend of his, Máximino Santiago, another carver whose work we have collected. This year, we purchased a lady dressed in the traditional pinafore-style apron, carrying a basket of watermelon slices on her head. Like Gabino, Máximino relies heavily on his carving for the support of his family. He has some land to till, “pero poco,” not much, like Gabino.

We drive up a dirt road that leads into the hills above Gabino’s house. Gary and I comment in astonishment when we bump over a tope on this rutted dirt road. “How could anyone go more than five mph anyway?” Gary asks. Dust, said Gabino, if cars go too fast, the dust gets into the surrounding houses. Dust in houses with dirt floors. A foreign concept for us.

We drive past fields studded with the dried remnants of the summer corn crop and finally turn off the dirt road onto a branch, even more narrow and rough. We stop along the road and walk up the trail to Máximino’s house. Gabino knocks on the front gate, which is made of the stamped tin used to form Jumex juice containers. A voice answers our knock and directs us to a minimal house below the road. We head down the trail and encounter several Santiagos, young and old. A small boy peers at us suspiciously from behind his mother’s skirts. Several dogs glance towards us and decide we are not worth a bark. We shake hands with a sturdily built woman with black braids and the beautiful coffee-with-cream skin of indigenous Mexicans. She produces a bag and pulls out several small carvings—a cat, a deer, and several spotted dogs.

Unable to refuse in the face of such hospitality and need, we selected a spotted dog, lying on his side in the c-shaped curl peculiar to resting Mexican dogs. After she wraps up our purchases, we turn to leave when she calls to us. “Sit down and try some champurrado, a chocolate drink.” Always open to a new experience, we follow Máximino into a low, shed-like building with a dirt floor. There is a wooden table along one side and two chairs, one plastic, the other a rickety wooden one with a straight back. This building houses the kitchen and dining room. Gabino drags in another and joins us.

The light from the single door and one glassless window lights the room. The seams in the tin roof also emit more light and let out the smoke from two wood-fired clay ovens in the other half of the room. Large comals, the flat ceramic griddles that have existed from pre-Hispanic times, sit on top of the ovens.

The señora sets steaming bowls of champurrada in front of us. I peer at the brown, viscous surface, taking in the rich smell of cornmeal and chocolate. A pre-Hispanic mixture of ground corn, water and chocolate, it tastes like thinned harina cereal mixed with weak chocolate flavoring. I find it bland for my taste, but very filling and warming. It seems like a good morning meal. I find that if I don’t drink fast, a crust forms on the top.

As we were drinking the champurrada, the señora brought in another bowl heaped with fresh tamales. I began to be concerned that we were eating their breakfast, but had experienced the generosity of these village people before. We find it respectful to accept the hospitality of people who offer. The tamales were blazing hot and were wrapped in cornhusks, unlike some of the Oaxacan ones in banana leaves I had eaten before. The masa lining was of finely ground corn, almost white, very soft and succulent. Strips of chile, chicken, and tomatoes filled the interior. They were delicious, a recipe for angels. There were no knives and forks, so we had to do a lot of finger licking before Gabino showed us the communal napkin, a piece of well-used cloth draped over a bottle.

As we went to leave, the señora wrapped up the last few tamales for us to take with us. We thanked her and drove Gabino back down the dusty road to his house. Ten topes later, we were back on the main road into Oaxaca, back to the modern world.

* * *

Gallery

Click directly on image to enlarge…

All Content Copyright ©2020 Linda Oman | All Rights Reserved