10. Sharing The Shade

Sharing The Shade

It is 4:30 and the late February sun is slanting across the mountains that surround the Oaxaca Valley. The courtyard in front of the Santo Domingo Church is almost deserted. Most tourists have retreated from the heat and are lolling under spinning ceiling fans as they sip Coca Colas, or taking siestas in their air-conditioned hotels. My shirt sticks to my back as I seek shelter in the foyer that leads to the cultural museum next to the church. I find some relief on a cool stone bench that stretches along one shady wall.

I sit back and contemplate dinner, wonder why my friends are taking so long touring the botanical garden, and debate buying that embroidered blouse I saw in the market. Interrupting my musings, a young Mexican girl of about eleven rounds the corner, pressing herself into the space next to me. I had noticed her earlier, scuttling among groups of tourists in the church courtyard, hawking several lackluster shawls draped over her arm. I have seen so many like her in my years of travel, the little ones who beg on the street, ghosting among the strangers, skipping past their childhood to help support their families.

Twiggy arms and legs, coffee-with-cream brown, poke out of a simple white cotton print dress. Clear plastic sandals reveal dusty toes. Coarse, untidy hair, its reddish tinge speaking of too much sun or too few vitamins, escapes her ponytail elastic and wisps about her face. Feeling the familiar tug when I am forced to face the inequities of life, I turn away and study the door, pretending that my friends will appear any minute, hoping she will go away. She bends over and peers at my face, looking intently at my sunglasses, pointing expectantly. Affected by the warm brown eyes in that somber face, I remove the glasses and hand them to her. She slides them on, turning to view the tinted churchyard. No smile of pleasure flits across her face. She hands them back.

In my high school Spanish, I ask her name. “Basílica,” she answers. She is named for the Basilica of the Virgin of Solitude, the most revered church in Oaxaca and my favorite to visit.

She tries her sales pitch on me, holding up two shabby white shawls. “Cómpralos,” buy them, she demands. Okay, I think, here is the pitch. I knew it was coming. I shake my head, my face turning hard again. She shrugs but doesn’t leave.

“Cuántos vendió hoy?” I ask, how many have you sold today? She holds up one finger and squirms back into the corner. She shows no fear, but looks me in the eye, seeming as curious as I am, evening the playing field with her directness.

She studies my face. Her eyes move to my blond hair. “Quiero hacer una trenza,” she states boldly. She wants to braid my hair. I stumble through excuses: My hair is too short. My friends will come. I have no time. Basílica insists with her hands, however, ignoring my excuses as small brown fingers reach up and remove my combs. She gently touches my hair. “Qué suave!” she says with surprise in her voice. How soft. She pets me as if I am a cat. I look at her ill-tended, damaged tresses with sadness.

Resigned, I turn my head and she gently slips off the band that holds my ponytail and combs my hair with her fingers, dividing the strands into three bundles. It doesn’t take her long to braid my meager locks. She wraps the band over the end and smiles as she surveys the results. I can feel the escaping wisps, the uneven weight of the braid, but I thank her and a smile finally warms her somber face. She pats my hair and rises to leave. Basílica waves and skips off across the flagstones of the sunny courtyard with her shawls across her arm. I wear my droopy braid for the rest of the evening to help me remember the touch of those small hands that brought our worlds together for a while.

Basílica has continued to be a part of my Mexican life. I returned to Oaxaca one year to be introduced to her young husband, Luis. The subsequent year she walked into the courtyard with a tiny baby wrapped in one of her shawls. Sadly, her child Gabriela was born with club feet, which we found out about through the courtyard grapevine. The ladies from her village had taken my husband aside one day to tell him that Basílica had been a bad mother, that the club feet had been caused by keeping the baby wrapped up constantly without exercise. Further, she hadn’t taken the child to a medical clinic for help. But this was just gossip. Clearly, this very young mother cherished her little one.

Over the years we followed the child’s progress. What she lacked in physical strength, she made up for in determination. She had a strong spirit, apparent as she dragged herself across the courtyard, or rode her tricycle to keep up with the other kids.

Over time, Basílica’s extended family migrated from their village high on the mountains to support their growing numbers. While Basílica continued to hawk her wares, cousins and aunties would take turns tending to the child, or playing with her. This community knows how to lighten the load of a mother, still herself a child.

After our last absence, Basílica had been waiting for my husband and me. “I knew you would come. Can we have a popsicle?”

* * *

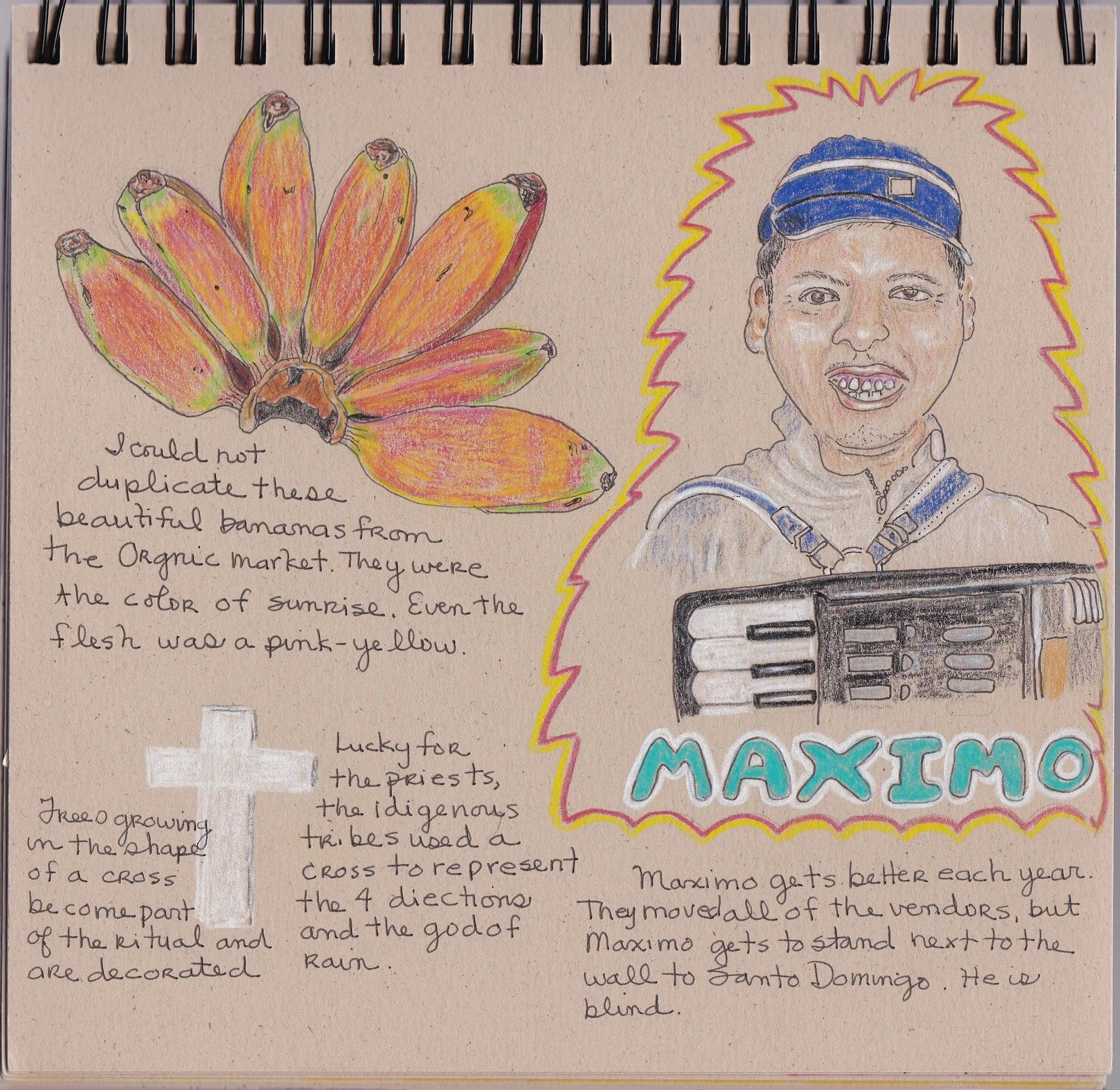

We encountered our musician that same year. During the month of February, we live in a small apartment that is not far from the Santo Domingo Church in downtown Oaxaca. It is a ten-minute walk from our compound to the Zócalo, the center of town. As we headed home one day when the temperature had climbed into the eighties, we heard some very bad accordion music wafting towards us from the next block. Now, to me, good accordion music is an oxymoron. It always reminds me of my parents and the weekly hellish journey into the realm of Lawrence Welk when I was growing up. I find I can tolerate it in the music of northern Mexico. Its polka-like rhythms backed by various sizes of guitars, is cheery and makes you want to dance or move.

This was not northern Mexico, however, and this musician was missing notes and slurring the melody so that the tune was almost unrecognizable. As we neared the green stone wall along the edges of the courtyards of the museum, we could see our torturer, standing in the narrow slice of shade along the west side of the street. Probably in his twenties, he was stocky, with the soft body of a person who doesn’t move around much. He was wearing a white, long-sleeved shirt and dark pants with a pair of black, carefully shined shoes on his feet. His full head of black hair shaded his face as he bent over the accordion, trying to coax the right notes from the keyboard as he squeezed away with his arms. It was a losing battle. We had to give him credit for effort, so Gary dropped some coins in his cup. As he looked up, his eyes had the unfocused look of someone who looks out on a dark world. He was blind. I felt the inevitable wrench when I am faced with poverty and hardship in Mexico. Here was someone barely making it, earning pennies on the street.

As the days passed, we frequently took the walk along the Alameda promenade. Most days our barely musical musician was there next to the green stone wall. He seemed to arrive mid-morning and leave with the sun. We never failed to drop a coin or two in his cup. He always looked up and smiled.

On our last trip to Oaxaca we headed for the Alameda. There was our accordionist. He had improved from last year. Most of the time, he hit the right notes and there was a jaunty confidence in his playing. We dropped our coins and were rewarded by the wide smile. My husband, fluent in Spanish, started up little conversations. He might ask him to play a certain tune or compliment him on his improved playing. We always stopped and listened till the end of the song.

I wondered about his life. When he tired of playing, he would just stand in one spot. We never saw anyone near him, maybe a parent who dropped him off and picked him up. He had nothing other than his accordion. What did he do for lunch? How did he get home?

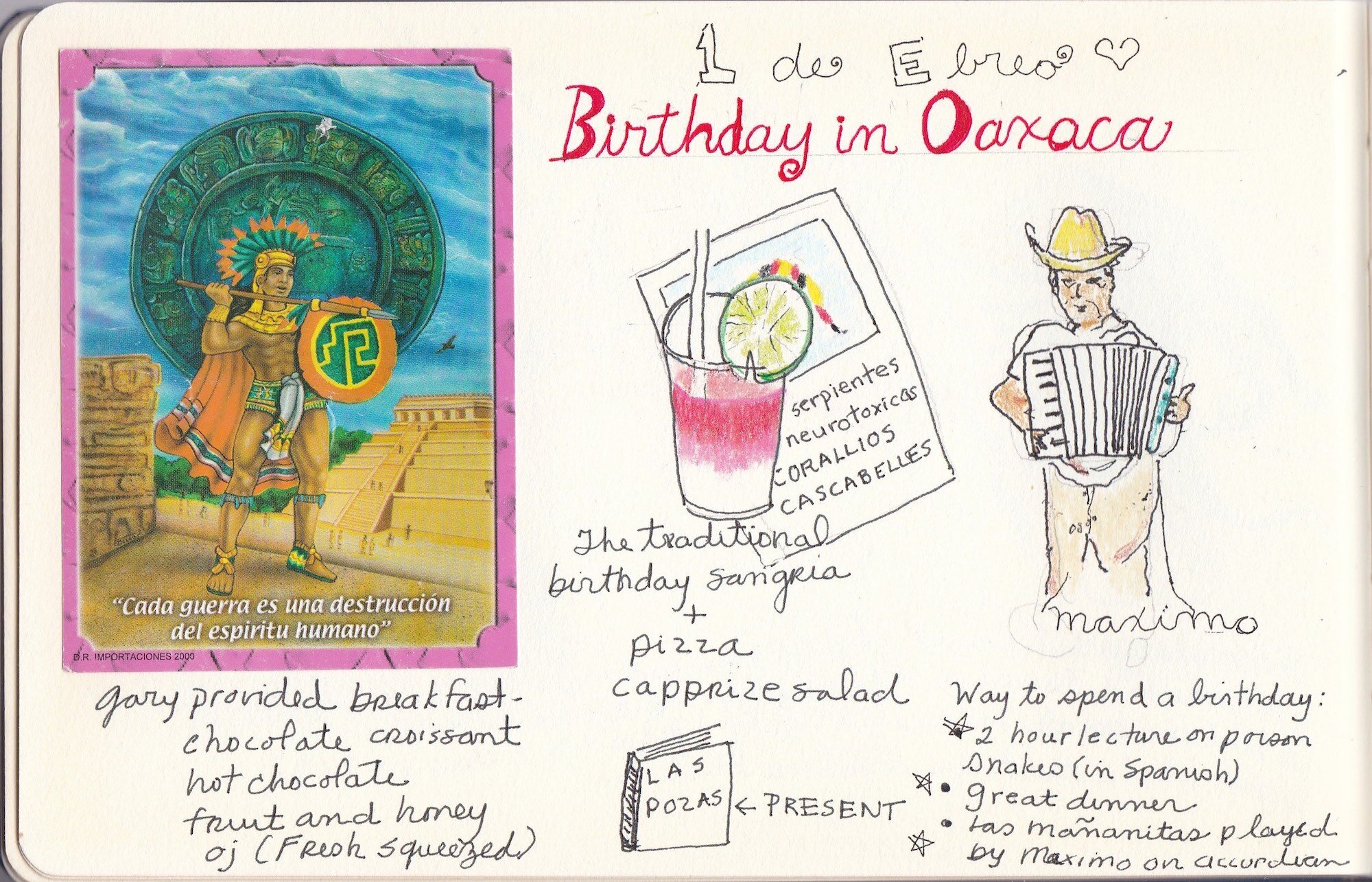

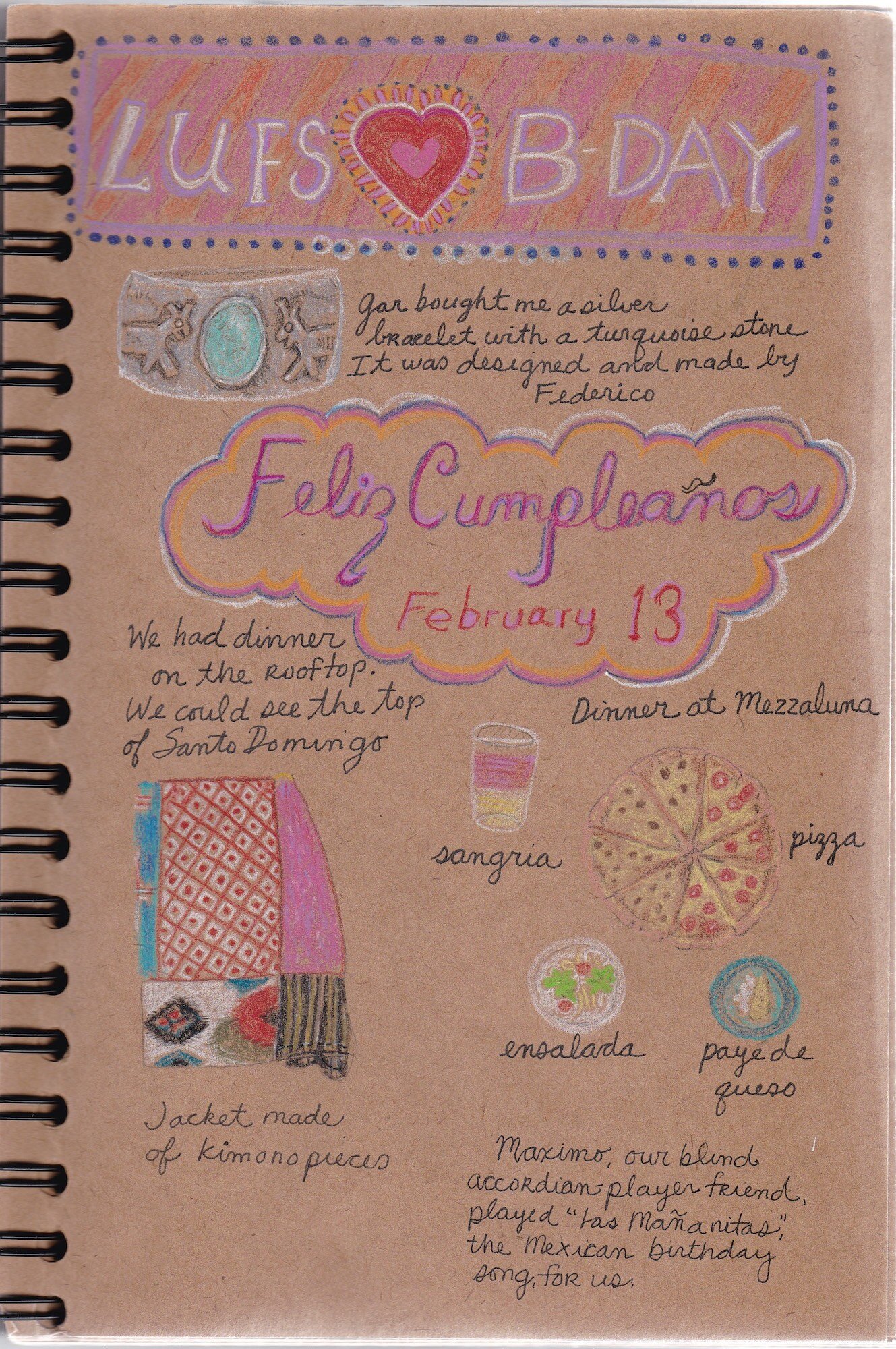

Our friend became a friend and we always made a point of stopping. Finally, on the day we were to drive north, Gary asked him his name. A smile split his face as he paused in his playing. “MMMMMáaaximo,” he said, drawing out the initial sound. His face was radiant. For us, he was the maximum, a survivor on the streets that traded cheery tunes for a few coins so he could support himself, and possibly his family.

* * *

Gallery

To scroll through slide show, click on thumbnails or arrows…

All Content Copyright ©2020 Linda Oman | All Rights Reserved