7. Guardians of the Sidewalks

Guardians of the Sidewalks

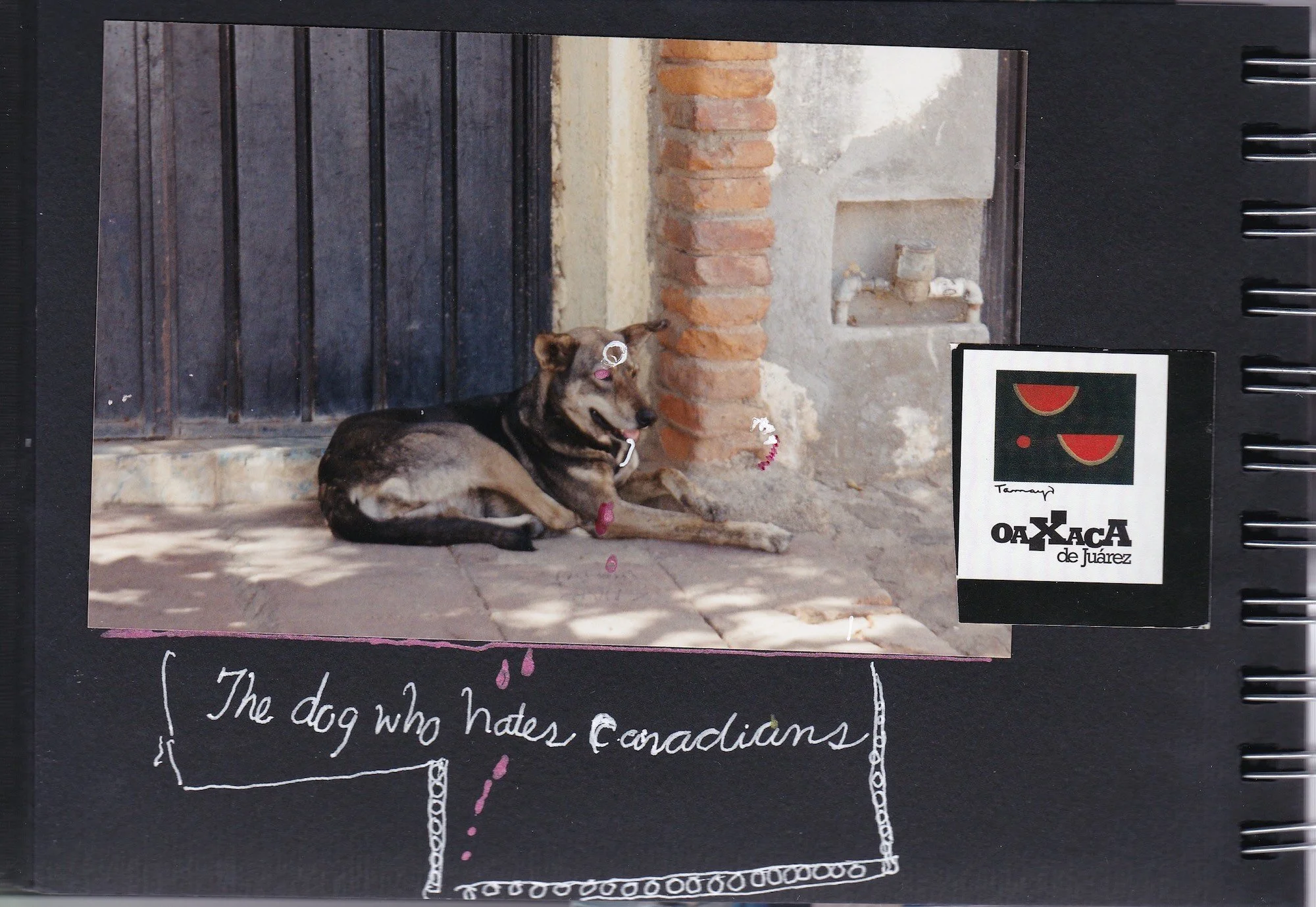

He lies on a pile of dirt in the middle of the cobbled street, soaking up the warmth of the stones as the evening cools in Bucerías, Mexico. Lean, the color of the earth, tough as the cobbles beneath him, this prime model of Mexican dog is a survivor. Dodging cars and thriving on old tortillas and chicken bones, he pays homage to Darwin as he protects his gene pool in this harsh environment. As we pass, he opens one eye, checking out these territorial invaders. We walk on two legs rather than four so he goes back to sleep.

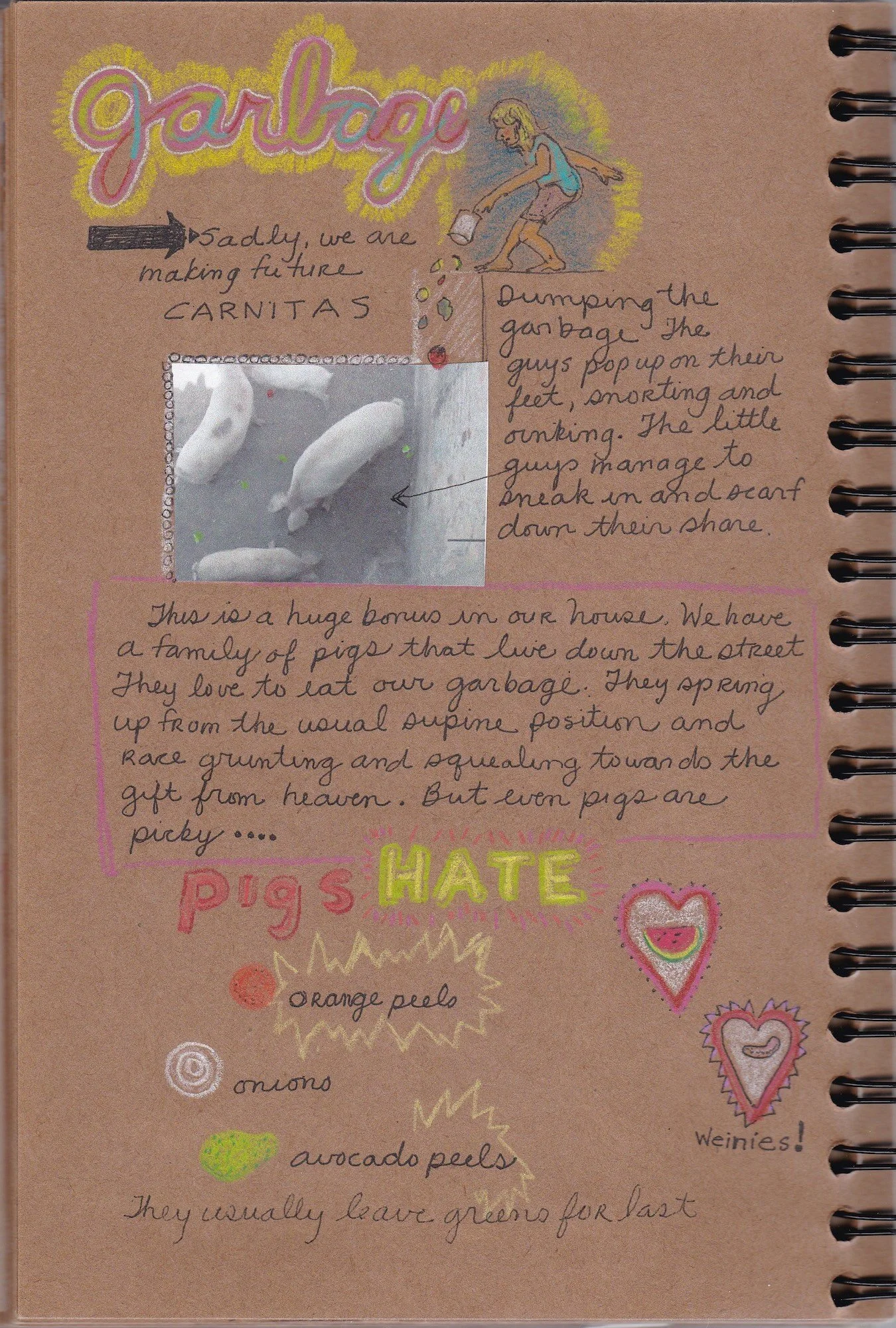

When my husband and I first visited Mexico thirty years before, we noticed a striking similarity among village dogs. Long-legged, brown, slim as greyhounds, they were masters of the eye-corner glance as they tucked their tails between their legs and belly-slunk off around dusty corners. We saw them atop piles of garbage, worrying the refuse and munching on second-hand snacks that seem to do little to fill out their hollow flanks. They lurked behind the food vendors’ stalls, waiting for the bits of fried pork or careless slops from a casually rolled tortilla to fall to the ground. Although we ached for these hard-living fringe-dwellers, we knew enough to give them a wide berth and to never extend a hand. “Pretend to throw a rock if they approach you,” the guidebooks advised.

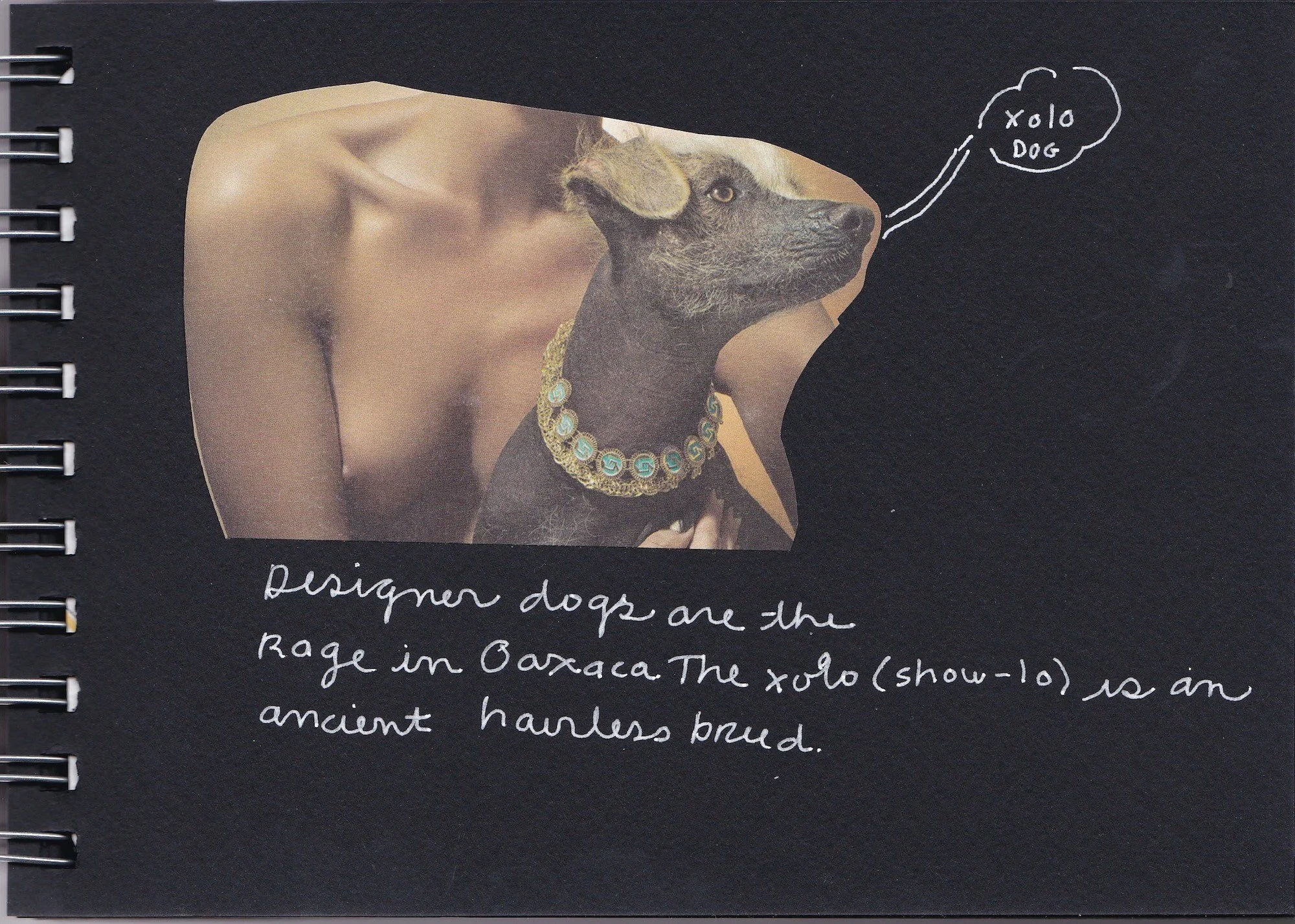

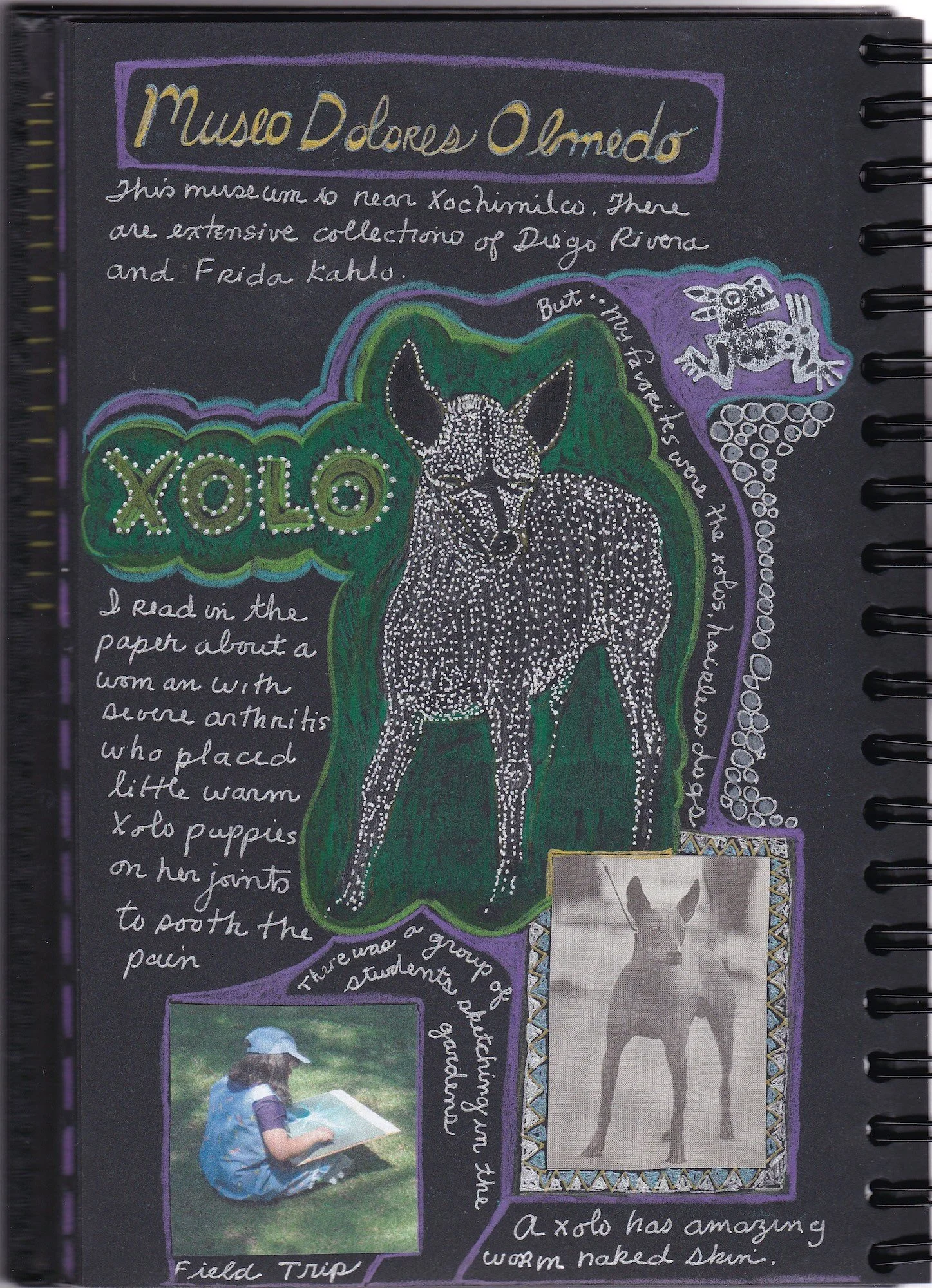

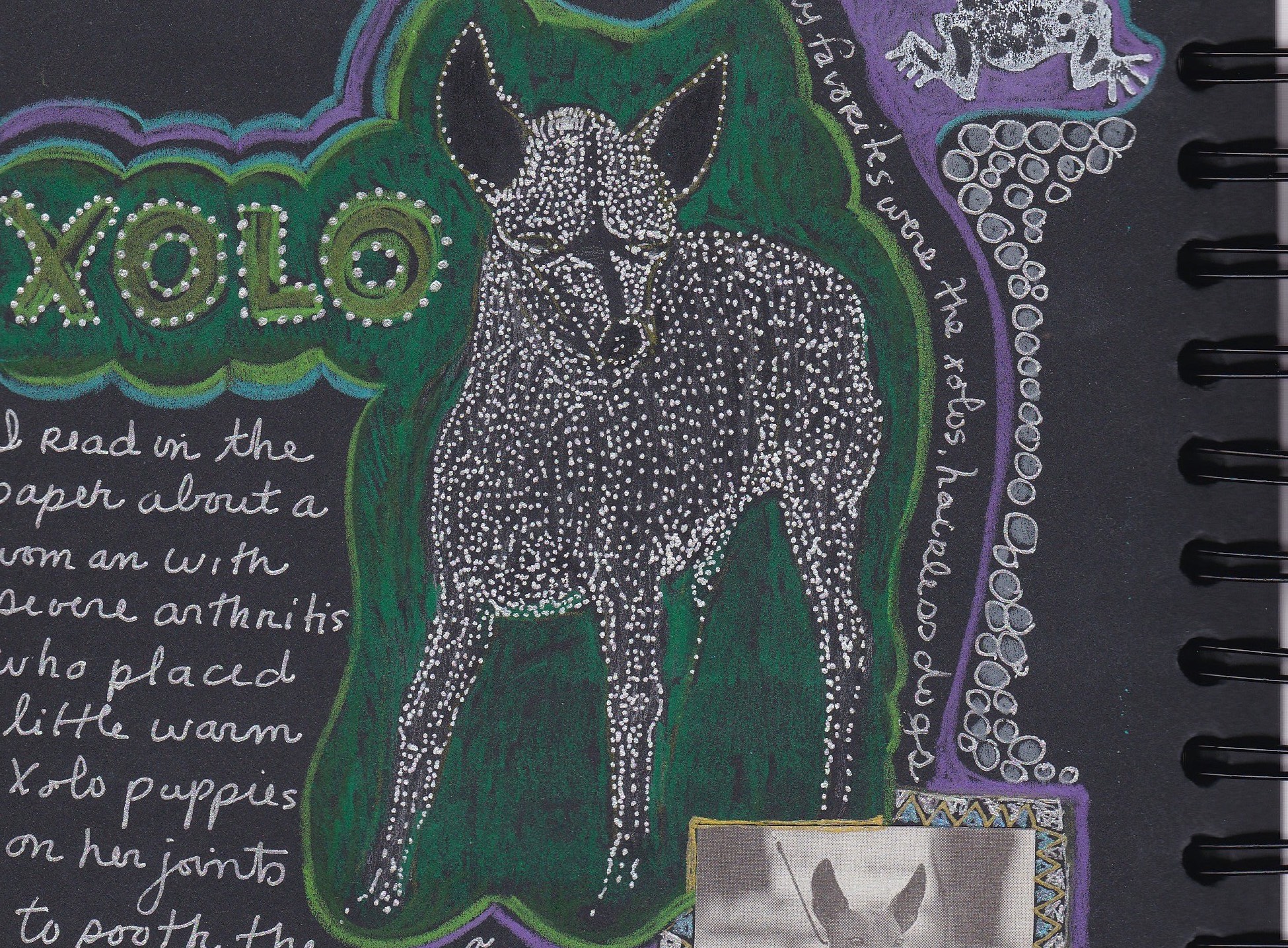

These tough specimens were a far cry from the ancestral stock I had read about in history books. The ancient Aztecs pampered and fattened up their little hairless dogs, the xolocicuintle. Revered as sacred guide dogs thought to lead souls through the dangerous territory on the way to the Aztec underworld, they were often buried with their masters. They were also sold in the markets for food as the Aztecs prized their juicy, tender flesh.

When Cortez swept into Mexico in search of gold and glory, he brought with him a powerful weapon, the mastiff dog. The Aztecs, accustomed to the plump little xolos, were terrified of these huge, slavering war beasts. As my husband and I swept into Mexico in our VW camper in 1968, we encountered their modern-day equivalents. One time, as we casually strolled through the rather posh suburb of Pedregal in Mexico City looking at the beautiful houses, we performed a mid-stride leap-for-life duet as a giant chorus of barks erupted from above us. Not only did the mansion have iron gates and high walls topped with broken glass shards, the roof was the domain of the killer guard dogs. Looking down on us from their heavenly perch with teeth at maximum extension, these dogs were definitely as huge and slavering to us as any Spanish mastiff.

As we returned to Mexico on many subsequent expeditions, we learned to redefine our concept of dog in a Mexican cultural context. During a summer stay in Guadalajara, we asked our host family the Spanish word for pet. The closest equivalent they could give was “mascota,” or mascot. The American concept of pet was foreign to them. Dogs either performed a function or were beneath consideration.

As the years passed, we encountered many of the Mexican classics of the fierce and slinking varieties. There were exceptions, however. Vino Solo, He Comes Alone, was one. One winter, we were traveling through north-central Baja, a beautiful but very isolated area dotted with exotic boojum trees and giant cardon cactus. We stopped to camp near Cataviña, a tiny settlement in the middle of the desert. As we began to set up our tent, a Mexican classic strolled up. We eyed the car door, ready to leap to safety, and looked for handy rocks. The wagging tail and friendly gaze eased our fears. The campground owners told us that Vino Solo had wandered into the campground several years before. They had no idea how he had crossed the desert and found their home, but he rapidly became a part of their lives. Although he was deathly afraid of cows, horses, and especially coyotes, he loved people. He adopted our camping party, snacking on our granola, and getting his loves from everyone.

We have traveled Mexico’s roads and loved her people and culture for over thirty years, and, if a country’s entry into the modern world can be measured by the state of its dogs, Mexico has come a long way. On this trip, I notice that a new layer has been added to Mexican dogdom. These are the dogs with collars, pets of the American kind, even out for exercise with professional dog-walkers. Pampered purebreds such as poodles and sharpei, wait to add their genes to the Mexican classic strain. A deadly-looking mastiff patrols the street near the beach, swaggering past us, looking for interlopers. I find myself hoping he will find some lovely poodle or friendly golden retriever to dilute his fierce genes.

Strays still haunt the streets and alleyways, but, since the pet revolution, there has been a visible explosion of back-street genetic engineering. Giant spotted heads on corgi-like legs, long-legged furry guys with shepherd ears and blunt snouts, these animals attest to an influx of foreigners. Several generations of Scottie-like black mongrels with tiny legs and floppy ears trot the streets around our hotel in Bucerías.

As we walk back up the street to return to our lodging for the night, our Mexican classic is still at his guard post. Further down the street, the remains of a garbage bag and its scattered contents give us a hint as to his evening activity. He doesn’t stir as we pass. The classic Mexican dog still dreams of conquest.

* * *

All Content Copyright ©2020 Linda Oman | All Rights Reserved