2. The Way South

The Way South

We have been going this way for so long. After 40 years of driving to Mexico, things change, and for some reason on this trip I was aware of all the landmarks on the way south from Seattle. The first are the Satsop towers on the nuclear reactor on Highway 101. Surprise. They have been decommissioned. The sinister cement towers with their caps of steam have been reduced to innocent-looking walls. Back on I-5 we pass the billboard in Chehalis with all of the right-wing messages. This year it is more innocent, a message about wise men and Jesus at Christmas time.

I never quite get over Palm Desert. The television spews forth advertisements for botox, and all kinds of devices that replace ailing body parts—the chair that lifts you up, the latest in walkers, zooming wheel chairs. A local doctor pushes his inflatable back support that is both hot and cold, as you like it. You can get an “All-porcelain smile makeover for $2,999” from David R. Perrone, D.D.S., or Medicare-eligible seniors can work with Dr. Tsu-Yi Chaung. There on the television screen on Saturday night is Lawrence Welk, reincarnated with his syrupy music and botox hairdo. Frank Sinatra croons from another choice station. If you so desire, you can watch the real estate channel and tour the latest and chicest in the valley. Live in a gated horse community alongside Merv Griffin where you can have your favorite steed right next door, in a compound with “A-list celebrities.” Have an infinity pool, a sub-zero fridge, marble everything.

Even a trip to the Saturday street market at College of the Desert is a trip. Golf club cozies in the shape of cartoon characters, sequined hats, it-chops-it-dices-it-shreds wonder devices, oils to rub on aching knees, colon cleansers, all the Palm Deserter could desire. There was a new booth this year advertising mortuary plots. I tried to avoid the Julia Robert’s smile of the woman in the gray pantsuit who tried to catch my eye. I followed a woman in a fur-trimmed sweater, knee-high, shaggy white boots with heels, and the requisite platinum puffed and motionless pile of hair.

Even the familiar Costco was a trip. I got my favorite tomatoes, found a paperback, and Gary got a giant jar of mixed nuts for our journey. As we were leaving, the glittering crystal chandeliers caught my eye. But it was the next display that gave me a shock. Coffins. Not the whole coffin on display, but discrete slices of coffin, pastel shades, looking like a cake decorator had frosted the edges. I have been to Mexico innumerable times, have seen the real thing, big seven-footers set up on the sidewalk in front of the funerarias, but passing a display while exiting Costco with my box of tomatoes, I am stunned.

I awaken in the morning to a powder-blue sky as the sun rims the desert. I go for my walk past the endless rows of pink houses with red-tiled roofs and identical palms and petunias, along the edges of the groomed green of the golf course. The air is dry and this January day heads towards a promised 76 degrees. Outside the walls of this oasis, I know that the valley is still there, that I can hike into the hills, ride a tram to the top of the mountains, find a rattlesnake or a scorpion, and I soften my view of this city of wide streets and gated communities. It has a harsh surface, but that is just one of the layers. When the wind blew the other night, it swept in the desert, the particles of sand, the yellow flowers that grow in the wild space. People come here to see the sun, to ease aching joints, to dip into the harshness of the desert.

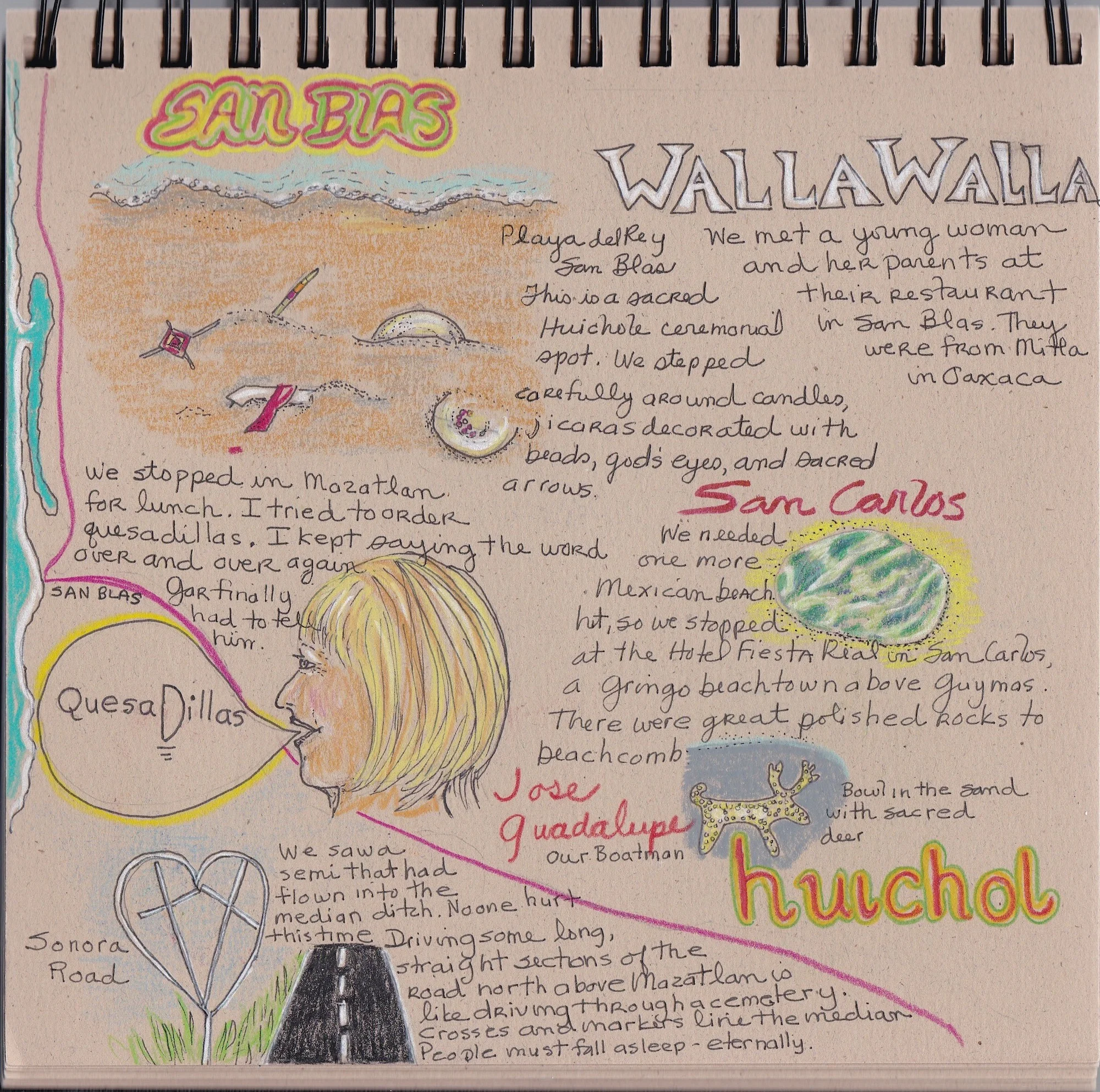

Released Into Mexico

The trip across the border at Nogales is quick and easy. You are in Nogales in Arizona and suddenly you are in Nogales, Mexico. The day is equally hot on both sides, the vegetation deserty and dry, but the transition to a different culture is immediate. The newspaper vendor with a pile of Imparcials who walks the narrow space between the lanes of traffic. A churro stand where the vendor turns the crank to produce a toothpaste-thick finger of sweet dough, which fries in the hot fat on an equally hot day. Kids in school uniform, white shirts, navy pants or skirts, giggling and chattering as they head to class. A man in a dark-checked shirt and a baseball cap bending over a tire in a dusty llantera shop, repairing tires. A brown arm stretched out an open car window to fling an empty paper cup out to join the glinting pieces of green, amber, and clear glass along the roadside. Plastic impaled on barbed wire stands at attention and waves in the breeze as cars pass. “Chickylandia,” also known as KFC, down the road from a plaster statue of a haloed saint in brown robes in a stone niche above the road. A man opens his door in traffic to spit on the pavement. We are in Mexico.

I feel so lucky to be able to drive the highways. It seems most people don’t realize Mexico is a beautiful country, not just the people, but the environment. We start at the border in the Sonoran Desert, a harsh area with lots of creosote bush and scattered cactus. As we head further south, the desert becomes more lush, with several varieties of cactus. The coast in this area is stark and beautiful, like Baja. The Sea of Cortez with its craggy islands that look like they have no vegetation lie offshore in a sea that can whip into white caps in no time. The beaches collect piles of shells, scallops, clams, conches, murex, and stretch in front of fishing villages and clusters of weekend homes. As we pass Ciudad Obregón and Los Mochis, the desert begins to give way to more leafy bushes and trees, but it is the fields of corn, acres of greenhouses, and endless crops that dominate the landscape. In January, we see a spotting of flowering trees that lose everything but their white or pink blossoms.

Towards Tepic, the air becomes more humid and we begin to see more jungle-like surroundings. Canopy trees, vines, large leaves. This intensifies as we wind downwards through the mountains to sea level. Our car passes through tropical forests with huge trees and ferns, strangler figs, kapok trees, a claustrophobic tunnel of vegetation that climbs and arches towards the road. Below Puerto Vallarta, it is dense jungle punctuated by giant trees that are solid with sunny yellow flowers that rain yellow blossoms on the ground underneath. But this largely gives way as we go down the coast to Costa Careyes where the dry deciduous forests begin. Leafless and dry in the cooler, dryer weather of the Mexican winter, this ecosystem is unique in the world.

Then as we drive toward Guadalajara, we pass between flat land that is a lake at this time of year. Frequent signs warn of tolvaneras, dust storms, that make driving dangerous during the dry times when the empty lake beds blow like dense fog across the road.

* * *

The High Road

On our first trip to Mexico in 1968, we drove twisting roads through endless towns. Lacking enough macho to pass on a curve, we crept along behind an assortment of leaning and twisted trucks billowing gray clouds of incompletely combusted diesel. Those roads are still there, but freeways, called “cuotas,” now provide an alternative for those who can afford them. On our last trip to Oaxaca in a car we rented in Mexico City, we splurged. We have discovered, however, that the concept of freeway has a distinct Mexican flavor.

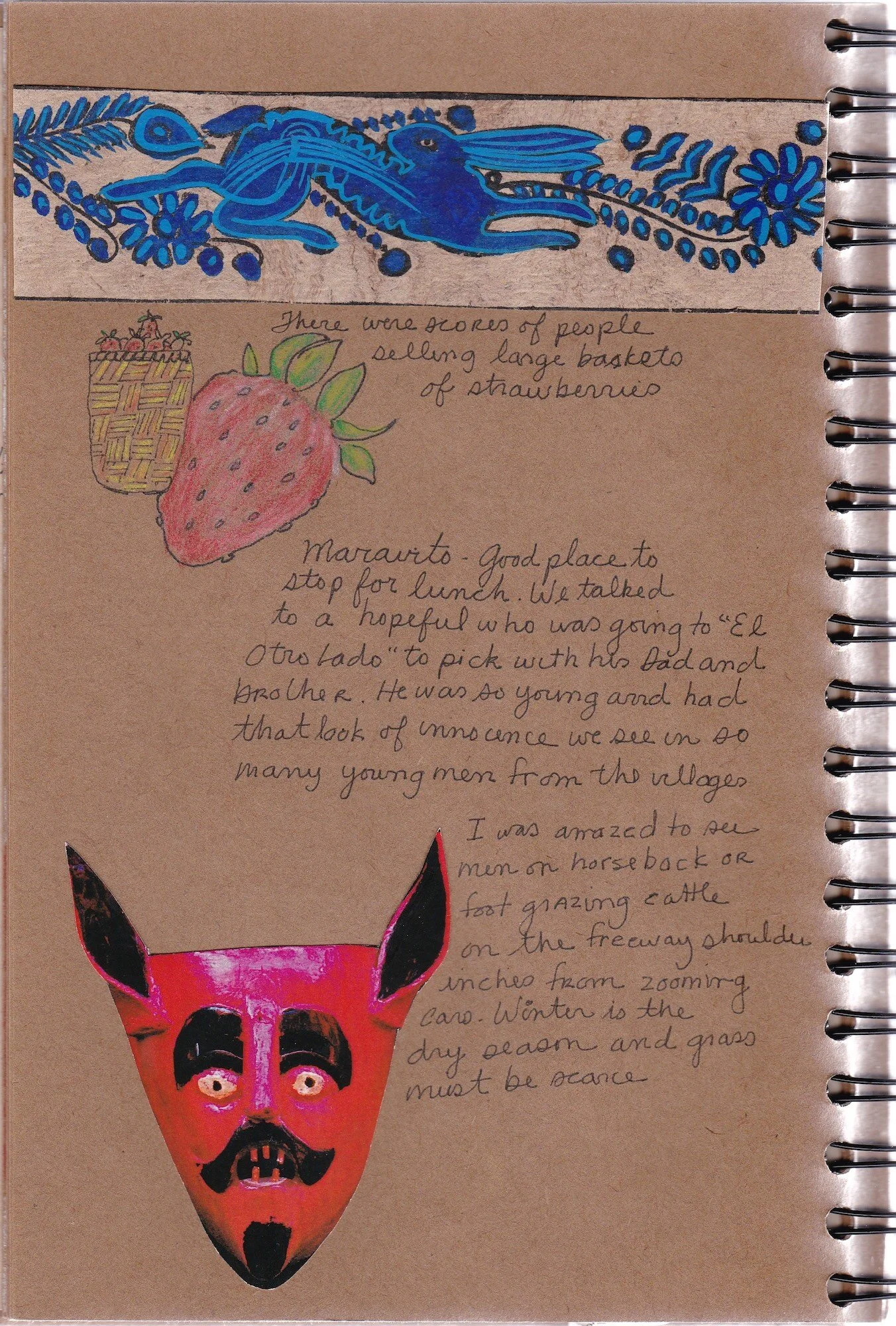

Freeways attract people who can pay. People who can pay have money to buy things. Vendors have learned this. As we drove out of Puebla, families strung out alongside the road waved hats to attract our attention. They were selling handmade kites in brilliant colors, some of paper, some of plastic, with streamers blowing in the breeze created by the zooming cars. There was a little girl in a red sweater in the divider sitting on a post. Her mother had long braids and a white apron.

As we left a toll gate, we passed young men in jeans and baseball caps holding up fuzzy brown puppies. This was probably a good venue as cars were coming slowly out of the toll booths.

Several times we have encountered bike pilgrimages strung out for miles along the freeway. Sag vans trail periodically and trucks with blankets and camping materials follow.

The freeway from Puebla has a yellow-striped crosswalk. There is a break in the median divider to let people cross. I guess the trick is to avoid the 70 mph traffic that never slows as you race for the other side. We watched a man make it across on a bike.

Chicken trucks pass by, piled high with plastic cages. A tomato truck stalled alongside the road. He had erected a pile of rocks to warn traffic, ignoring the “No deje piedras en el pavimento” signs designed to discourage the practice. Don’t leave stones in the road.

We pass water stations designed to look like old-fashioned wells. They have solar cells on poles above them.

A dirt road turns off the freeway. If you want to make a u-turn on the freeway, of course you use the wide space on the right side of the road.

The freeway as it leaves Mexico City has vados, the reverse of topes, speed bumps. Imagine going 65-70 miles per hour and hitting a huge dip in the road. They are designed to drain off water.

A freeway is being built that leads to Tlaxcala. We drove in at night, flaming barrels of petrol warning that construction was in process. A man stood in the middle of the road in an unlit section with light sticks to direct traffic.

“Alguien te espera, no maneje cansado.” Don’t drive when you’re sleepy. The divider down the middle of the road was a four-foot-deep v-shaped water ditch. I can imagine what would happen if you drifted in.

The anachronism. You drive along at 60 mph and pass farmers in their fields, plowing with horses or oxen. You are passed by Altimas, Mercedes’, BMWs, high-end SUVs. We fill up our ten-gallon tank—US$24—and wonder how some of the more modest vehicles can afford to drive at all.

It never fails to amaze me while whizzing down the four-lane freeway and we pass a man and his son, driving a wooden cart pulled by a lanky horse in the median ditch. He sits erect, classic Mexican farmer with his neatly trimmed mustache and straw cowboy hat. The wagon is filled with bundles, probably from a trip to Navajoa, about ten kilometers down the road. Double semi-trucks whip by, but he stares straight ahead, traveling at the pace of Old Mexico. A bike approaches, its rider wobbling along the six-inch space between the white edge line and the edge of the asphalt. He faces traffic, unperturbed by the narrow margin he occupies and the trucks that carry their own windstorms.

Then there are the walkers. Men with large garbage bags on their backs, collecting aluminum cans to sell for pesos at the recycling stations. Farmers collecting long yellow grasses in the medians to feed their livestock. South of Los Mochis as we pass miles of fields filled with corn, beans, tomatoes, endless crops, we pass women far from their homelands, women in long skirts and scarves wrapped around their faces to protect against the cold, coming to work in the fields or factories. Men in white rubber boots, out in the cold and fog of a January morning on bike or on foot along the shoulder of the freeway. Three men flatten themselves at a break in the freeway divider, ready to dash across to the other side when there is a gap in the flow of traffic. Farm workers huddle in the backs of pickups.

Just north of Mazatlán, we see our first red-slash-no-tractors sign on the freeway. In the USA, it would go without saying that you couldn’t crawl along, even in the right lane, in your lumbering tractor. They actually also have signs that say the opposite, no-red-slash tractors-okay. I sort of like that, the engineers and planners taking into account that their superhighways cut across miles of farmland. The farmers were there first, and sometimes there is no other way to get from one field to the other in your tractor.

* * *

Gallery

Click on image to enlarge.

All Content Copyright ©2020 Linda Oman | All Rights Reserved