18. The Dog That Barks

The Dog That Barks

As Gary and I walk along the trail that follows the irrigation ditch high on the side of the dry yellow hills of Oaxaca, I hear a dog barking in the valley below. I dismiss it, as we are well out of reach, but as I have always been wary of dogs—fierce, territorial Mexican mongrels in particular—it registers in my mind. The temperature is already in the eighties and the day, blue-sky perfect as we skirt the rushing water in the cement culvert.

We walk for about three miles, finally descending to explore the abandoned cement hulk of a hydroelectric plant at the head of the valley. The date 1953 is etched into the stone by the front entrance. We take a few pictures of the interior, entranced by the rays of sunlight that arrow through the holes in the roof, illuminating the rusting machinery.

When it is time to head back, we take the trail that runs through the shady trees in the valley floor. We are lulled by the peacefulness and beauty, the fiery red and orange lantana flowers, the kapok trees with bullet-shaped pods that burst in fluffy white explosions, spreading seedy snow throughout the valley. Water striders zoom on splayed legs in the pools formed in the almost-dry river. There are no houses or people.

The silence is broken by the distant sound of clanging bells. The rhythm is irregular and we recognize that these are goat bells. Soon, the leader emerges from the forest, a large white animal with yellow eyes. He veers off the path, leaping across the rocky river bed to the opposite side. A stream of goats follows him as the herd spreads out to graze on the tender grasses on the hillside.

We stop to watch the little ones with their matchstick legs and awkward gait trotting after their mothers. Then we hear a different sound, a bark in the distance. Quickly, the single sound becomes a symphony of excited yips and snarls, the din flying towards us up the trail. My body goes cold and I try to close the gap between Gary and me. With staccato blasts and growls, a half-dozen dogs swirl past us in the underbrush. Scruffy, leggy and muscular, these dogs take seriously their job of protecting the little goats. But surely the two gringos in shorts and billed caps are no threat. Wrong. Instead of heading up the trail to join their goat herd, the dogs turn and fan out through the bushes behind us, circling to attack as a unit.

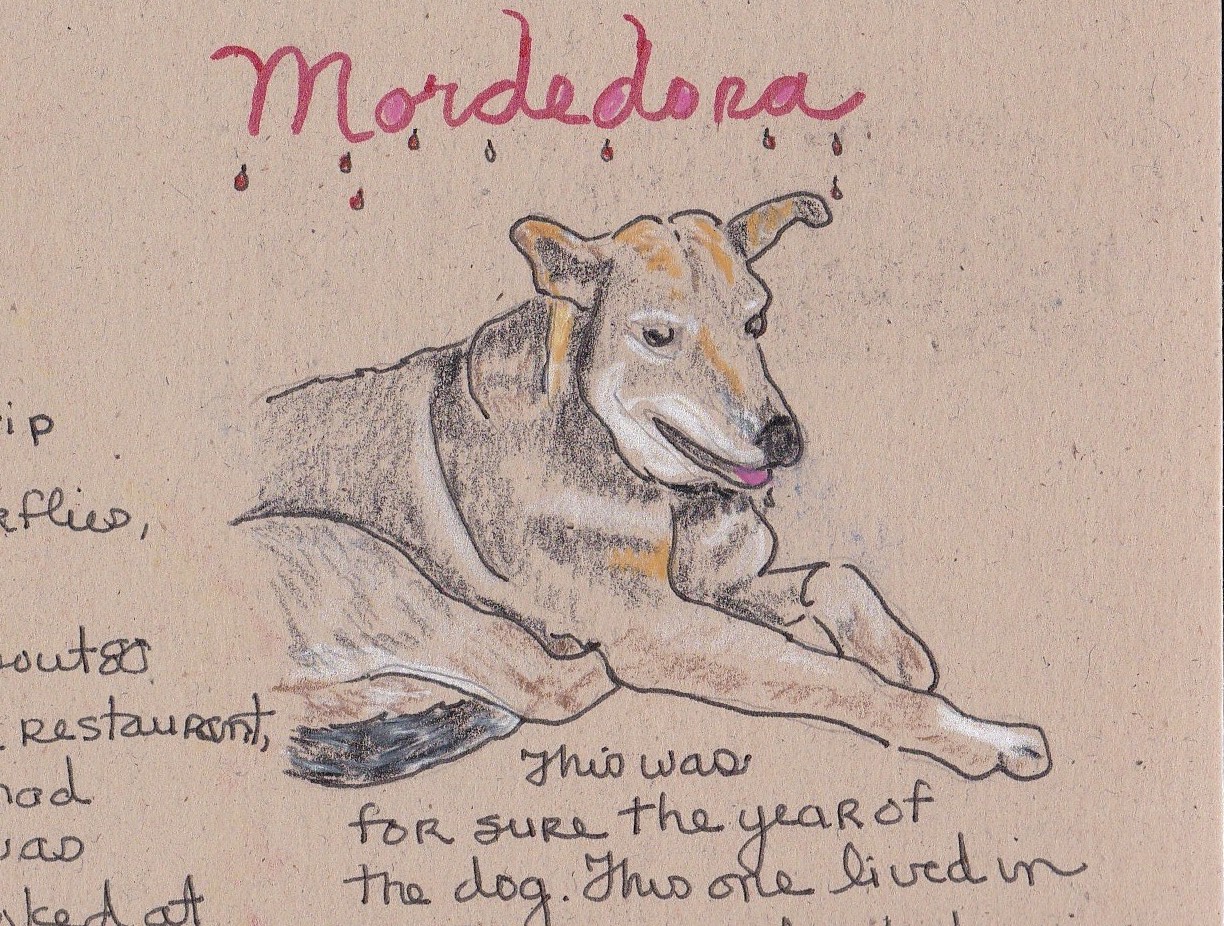

Gary quickens his pace, not to a run, which might encourage them, but a long stride that widens the gap between us. I turn to assess my attackers. A yellowish coyote-like cur, all gums, canines and erect fur, snarls and braces in a stiff-legged posture behind me; he balances on the edge of a lunge, jaws two feet behind my bare calves. I yell to Gary as my legs piston and I try to pick up speed while glancing over my shoulder at my attackers. “Help me, they’re right behind me.” My mouth is dry and the sound won’t amplify but he stops and we turn to defend ourselves. Several of the dogs have moved on after the goats, but the yellow alpha and his buddies continue to advance on us. I visualize the sharp canines piercing the curve of my calf.

Then we hear human voices and see two goatherds picking their way through the bushes. Our saviors gather rocks and aim them at the attackers, the classic Mexican way of dealing with aggressive dogs. Responding to their masters, the dogs turn and charge off in the direction of the distant goat bells. We thank our two rescuers and they head down the trail. With a bravado I don’t feel, my husband calls to them in Spanish, repeating a well-known Mexican aphorism, “Perro que ladra, no muerde,” the dog that barks doesn’t bite.

Suddenly, we see the yellow cur eyeing us through the bushes. “Ah, estás equivocado,” Oh, but you are mistaken, answers the herder, a faint smile on his lips as he shoulders his bag and heads up the trail.

* * *

All Content Copyright ©2020 Linda Oman | All Rights Reserved