16. Gallo

Gallo

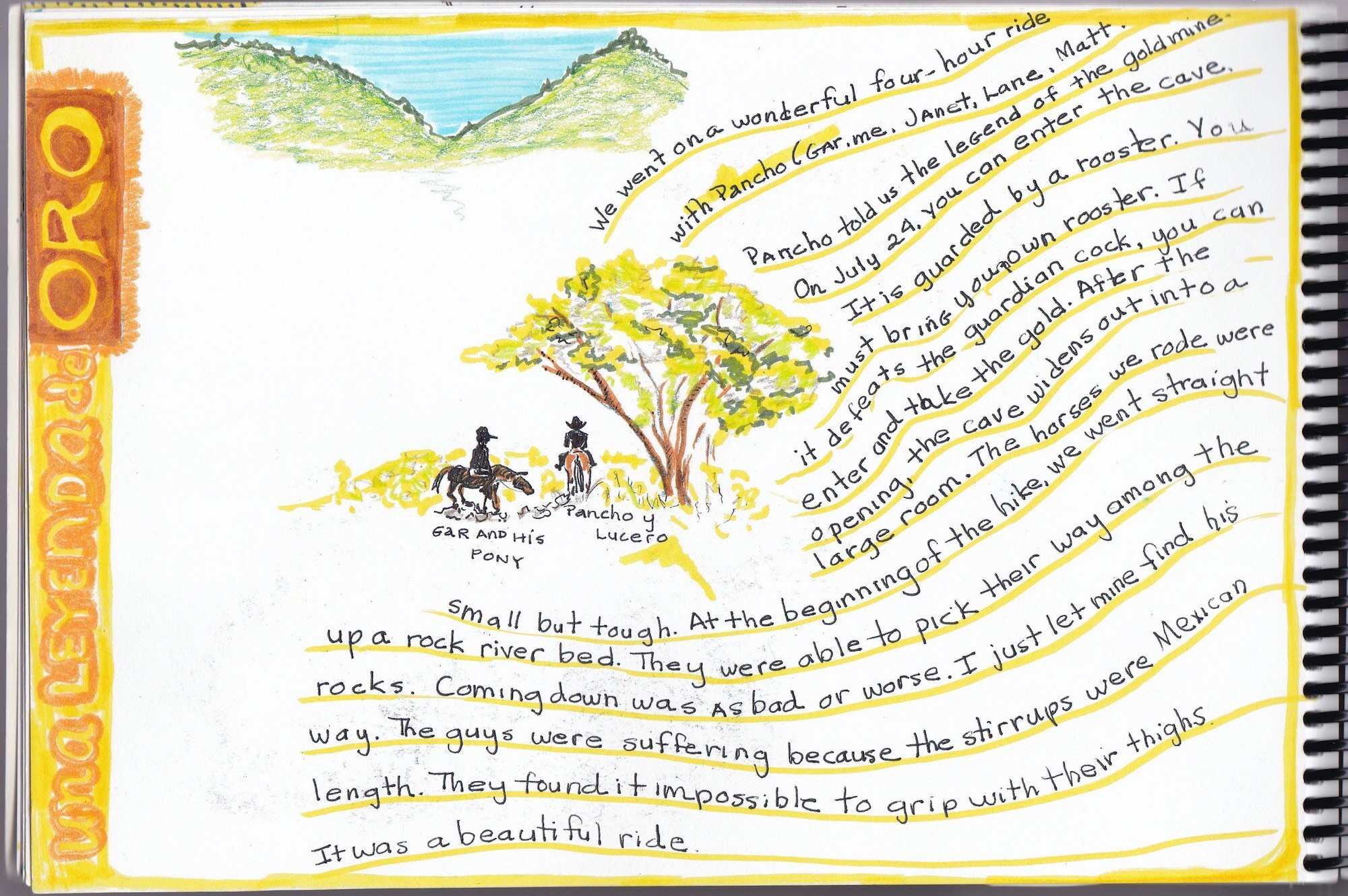

As Gary and I stepped out of the taxi into the warm Mexican night, I was relieved to see a clean, modern building in front of us. This looked a lot better than I had imagined. It was Saturday night in Guadalajara and we were about to see our first pelea de gallos, cockfight. We had never witnessed a bullfight, so when one of our expat friends suggested attending this other traditional spectacle, our curiosity was piqued. In comparison to bloody bullfights, it seemed a competition between chickens had to be a gentler experience. Our expansive curiosity was always leading us down unfamiliar corridors in an effort to understand the fullness of Mexico’s culture. And yet this evening I was aware of a growing sense of unease.

We entered the building, walking past the guard at the front gate. A guard? Why do chickens need a guard? We were about to find out.

Brought to the New World by the Spaniards, the sport of cock fighting was initially a gentleman’s sport, patronized by high society during the Colonial period. Wealthy landowners used any excuse to stage a fight. A fiesta or a birthday brought out the specially bred cocks and the wagers were high. In the more democratic Mexico of today, cock fighting matches are open to all. Many towns have special arenas called palenques.

The interior courtyard of the Guadalajara palenque looked more like the lobby of a hotel. People gathered in friendly groups around a bubbling fountain or chatted at tables in the patio restaurant. After we bought our tickets, we joined the crush as spectators filed into the arena. We took our seats on the hard wooden bleachers, choosing a row far from the more graphic action, and from a safe distance looked down on the small ring below. A blue wooden wall circled the sawdust-covered central area. I was to find out that this served a vital function. Not only did it keep the furious cocks from racing off into the bleachers, it also protected the spectators from flying chicken bits. The courtyard restaurant extended out above the ring. Chicken-watchers could eat as they watched the action below. You could have a multi-sensory chicken dinner if you wanted the whole experience.

Upon checking out the crowd, I discovered that I was definitely in the minority, as most of the spectators that surrounded us were gallos, a Mexican word for a male chicken and also a slang label for “stud.” Dressed in pointy boots, cowboy hats, and tight Levis, they sat in perpetual drifts of blue tobacco smoke, talking blue-streak Spanish and flashing wads of pesos. An occasional borracho, a gallo filled with tequila or cerveza, wavered by, following the vendors that roamed the bleaches. A man in a well-stuffed white suit balanced a platinum blonde on his knee and reeled off pesos from a roll as he prepared to place his bets. There were even a few children, already bored, who invented games or played tag among the seats.

We could hear the chickens, waiting in boxes in the hall above the arena.They crowed out their territorial challenges to phantom chickens around them. Fighting cocks are bred for the battle alone. Only the sturdiest and most aggressive are selected for breeding. Cock farms gain reputations for their fighters much like racing stables, and serious bettors take into account the pedigree and training of the contestants.

Even though there was not a chicken in sight, other gambling had already begun. A short, brown man rolled a large roulette wheel into the center of the ring and took wagers. The bettor could either pick a number on the wheel or could bet on whether the number would be odd or even. The minimum bet was two thousand pesos, about ten dollars. These guys were serious gamblers.

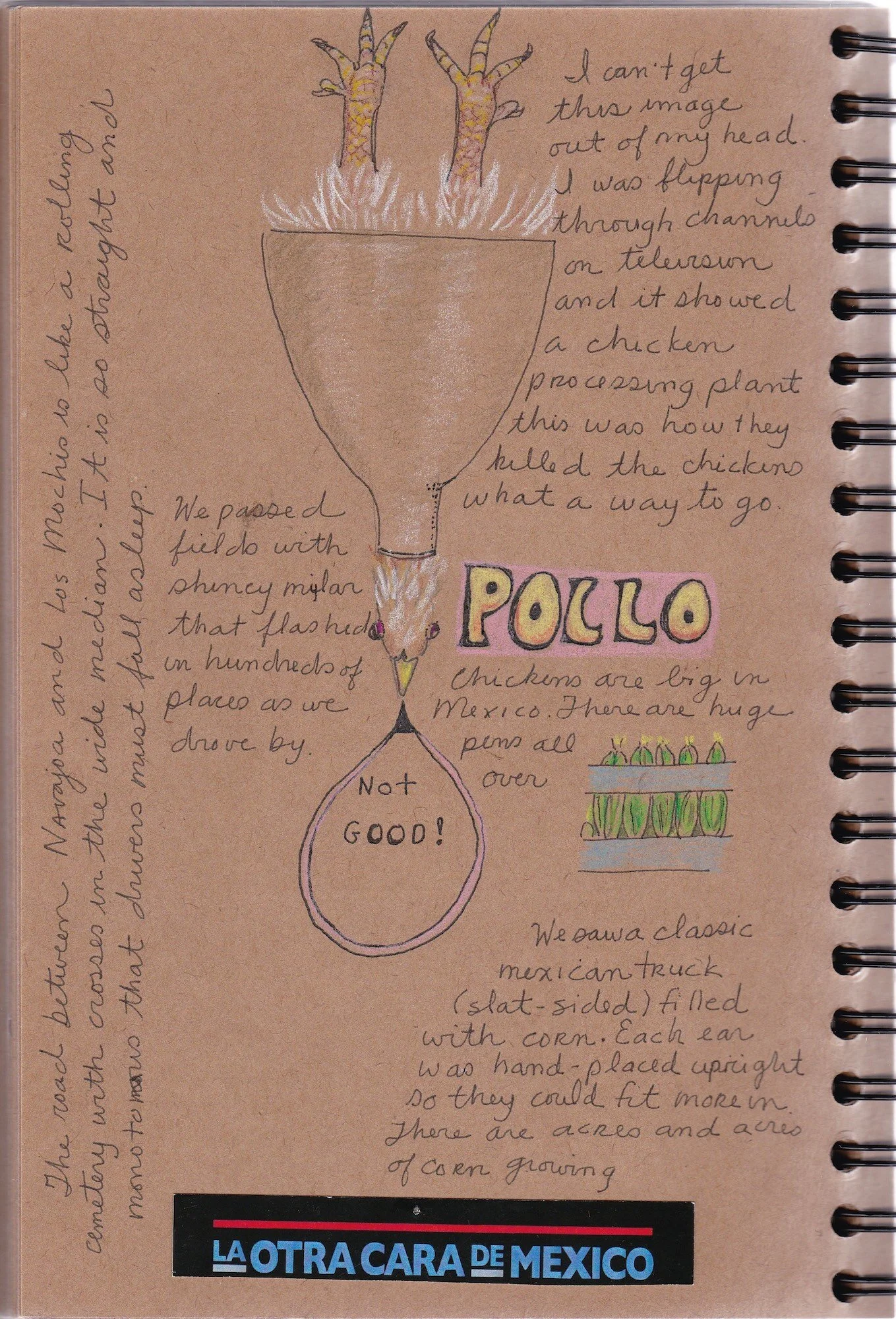

It was finally time for the main event. After an attendant removed the roulette wheel and raked the sawdust, two handlers entered, carrying the first pair of fighting cocks. To the uninitiated they looked merely like strong and healthy barnyard roosters, complete with drooping wattles and jaunty red tail feathers. The handlers turned the cocks so they faced each other. Holding them firmly, they lunged them repeatedly towards each other to build up the hatred in their little chicken brains. Sometimes a third cock, the teaser, was brought in to incite the fighters to further frenzy. “Gallos” now took on a double meaning as they were finally able to show their machismo.

The smoky haze intensified in the arena as the spectators puffed furiously and stared intently, trying to assess the fierceness factor of each cock. Which one was struggling to break the grip of his handler? Which stare was averted first? The betting began. As pesos changed hands, the referee moved in closer to the action.

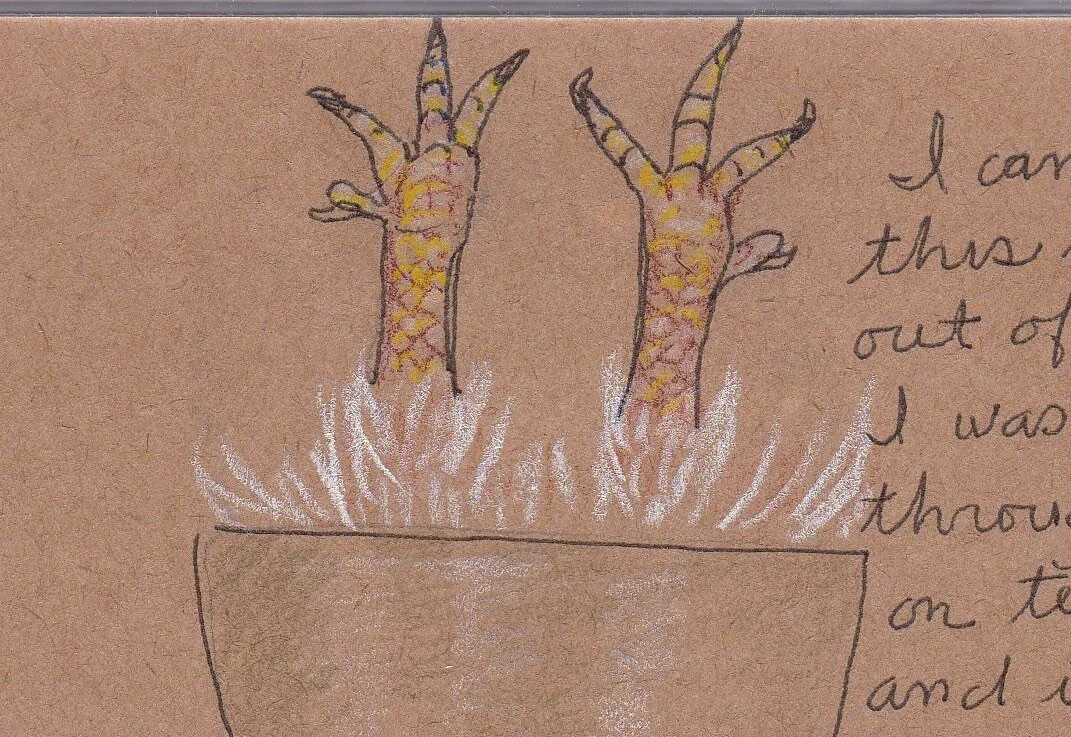

Holding the furious chickens under their arms, the handlers retreated to their wooden equipment boxes for the final preparations. They drew out a pair of deadly looking metal spikes, gaffs, binding them with leather thongs to the chickens’ legs. These were the murder weapons.

As the combatants were brought back out onto the floor of the arena, the handlers would occasionally blow on their faces or spit a mist of tequila onto their feathers. We never figured out the purpose of this action. It either annoyed them enough to kill or put them into a drunken trance so they would be fearless.

The betting now over, the handlers moved to the center of the ring, set the cocks face-to-face on the sawdust floor and retreated behind the blue wall. Neck feathers fluffed out in bravado and beady eyes locked. The chickens lunged toward each other. Wings flapped in fury as they kicked their legs high, attempting to drive the sharpened spikes into the breast of the opponent. They fell back under a rain of drifting feathers, gathering their fury for the next attack. Eventually one of the chickens fell to the floor, mortally wounded. Occasionally, the battle was over with this first lunge. Usually and unfortunately, it took longer.

If the pair survived the first few lunges, they were given a break. The handlers raced out from the sidelines, swept them into their embrace, and assessed the damage. If the cock was in a weakened condition, the handler sprang into action. Sometime he blew into the feathers as if he were inflating a chicken balloon. If this didn’t work, he licked the head or squirted his dazed charge with tequila. If all else failed, he gave the chicken mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, placing his lips over the chicken’s beak.

After the break, the chickens were at it again. Some of the fights were long and gory, both chickens dripping blood onto the sawdust of the arena. In others, a seemingly uninjured chicken would drop to the ground as if his wire had suddenly been cut. Usually, the fight was over when one chicken could no longer hold up his head. Swinging upside-down like a pendulum, the limp loser was carried out. He would become part of a stew, a sad end to a valiant fight. In this land of bull fights and gallos, I doubted if he was mourned.

We watched several fights before the dangling bodies and the brutality began to get to us. We weren’t there to judge but we found it hard to accept with the eyes of our own culture. As we walked out through the courtyard with its bubbling fountain, we passed the restaurant. Special of the day? Chicken. Bet it was tough.

* * *

All Content Copyright ©2020 Linda Oman | All Rights Reserved